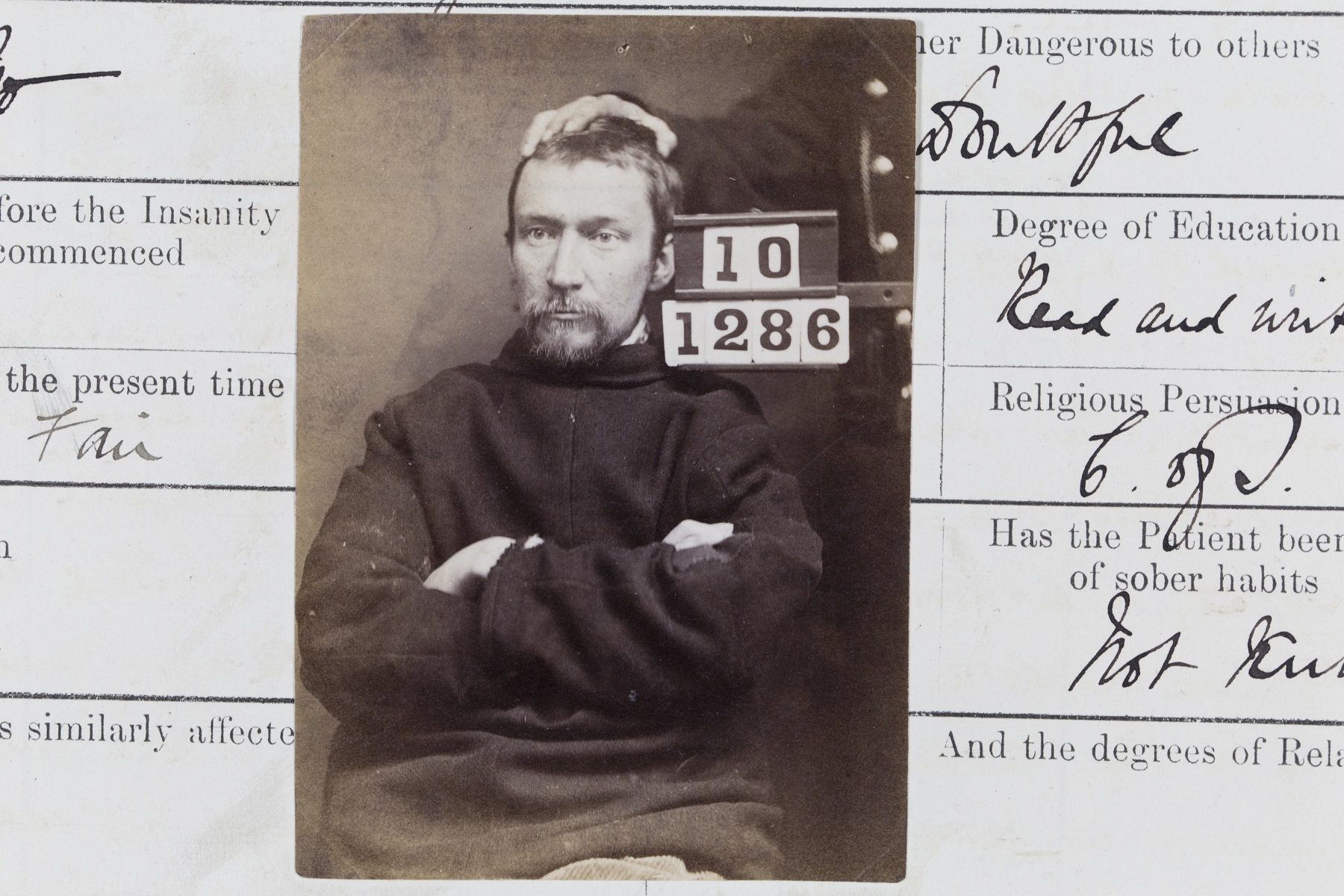

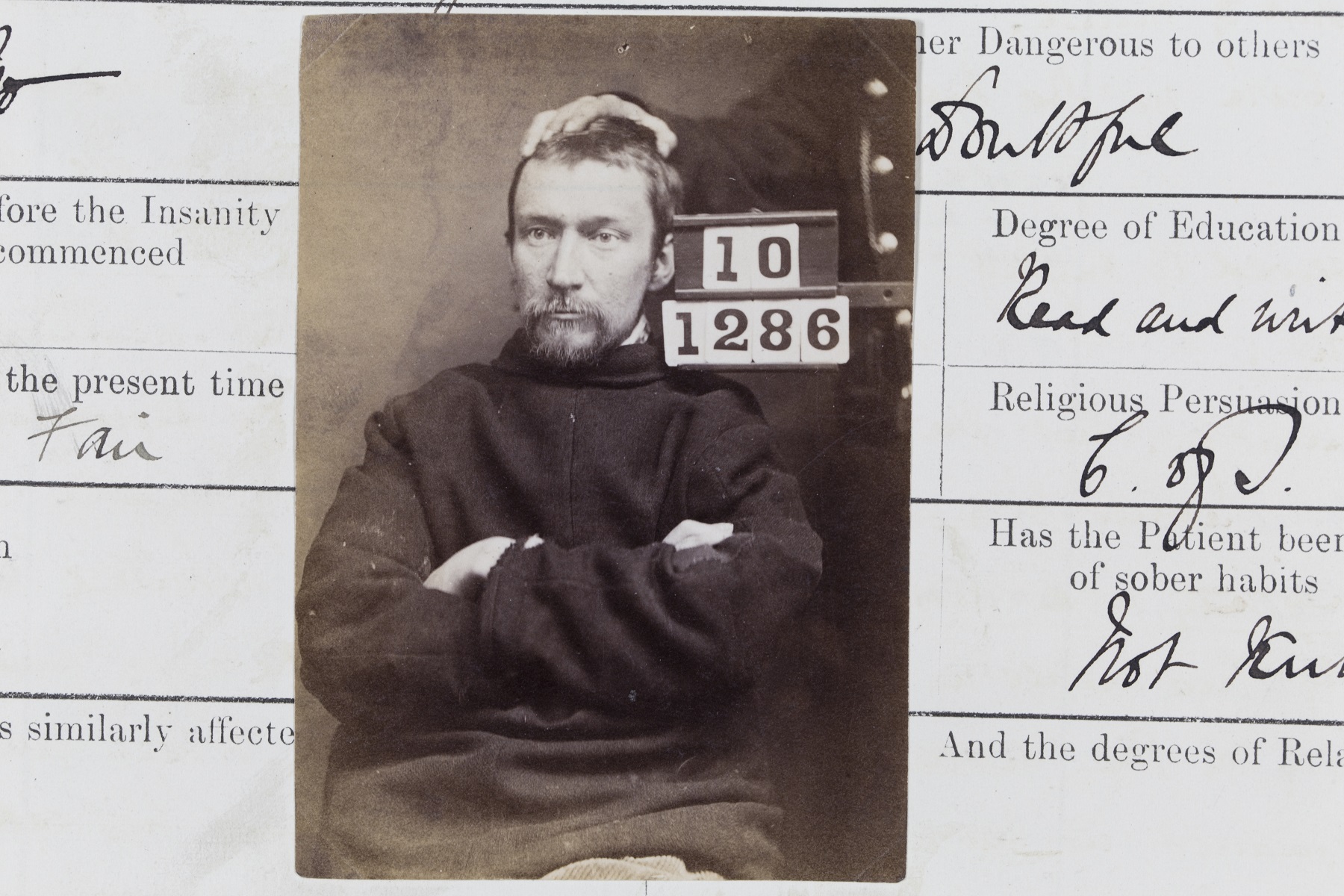

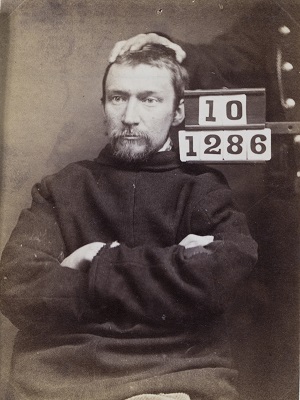

William Porter

Admitted 1881. Housebreaking and Theft

'A tall, thin featured young man. Form of insanity: general paralysis of the insane.'

The largest single category of admissions to general asylums in Britain c.1900 (about a fifth of all men) was for organic rather than psychogenic illnesses: acute biomedical conditions with secondary psychiatric symptoms. William had a neuro-syphilitic disorder, known as general paresis or general paralysis of the insane (GPI). Manifested in personality changes, social disinhibition and indiscretion, motor difficulties, and cognitive impairment, this condition was degenerative - and usually terminal. Not until the 1940s did antibiotics provide effective means of dealing with the bacteria, which caused syphilis.

Expert opinion on William's state of mind was divided. The physician of the Barony Parochial Asylum at Lenzie, Dunbartonshire interviewed him in Barlinnie prison, Glasgow, and thought he was faking, because he looked 'cunning' and showed 'sharpness and clearness and intelligence' when questioned. Visual signs like facial structure and expression were traditionally important diagnostic tools for doctors. His stubbornness in the face of authority, obvious in his photograph, may have influenced that assessment.

The medical superintendent of Perth prison also talked at length to William in Barlinnie and came to the opposite conclusion. He accepted him into the Criminal Lunatic Department (CLD) as 'of unsound mind', based on his indistinct speech, unsteady walk, and persistently held delusions of wealth and grandeur - all, for him, symptoms of GPI. He also argued that cunning, determination, and intelligence were not inconsistent with insanity, and that, while the prisoner daubing the walls with his own excrement could be a ruse, eating it was a sign of genuine derangement. In short, 'This man is insane and not shamming.'

The Victorian criminal justice system, medical professionals, and general public were all alert to the possibility of the accused pretending to be insane. Of 222 CLD admissions 1846-70, nine were eventually classed as 'feigned'. Yet counterfeit madness was hard to sustain in a crowded and closely observed setting. Prisoner-patients did not have to work, but otherwise conditions were no better than in the General Prison or any other penitentiary. An inspection conducted in 1857 found cells with one to four beds 'generally very gloomy...The windows are strongly barred, and...are generally placed high in the wall, beyond the reach of the patients. The doors of the cells are of great strength, and lined with iron plates, or studded with large iron nails.'

In addition, incarcerations at Perth CLD were indeterminate and in practice usually much longer than the average for those convicted of the same offence, but not deemed insane. Thus William spent three months at Perth, compared with a sentence at Paisley Sheriff Court of just one month in Barlinnie for his minor offence. Some of the insane women who had killed their children lingered for decades in the CLD, when the average sentence for their sane counterparts in a general prison was two years. Capital punishment for the offence was possible in theory, but unknown in practice in Victorian Scotland.

William Porter’s photograph from the Criminal Lunatic Department Case Book

Credit: Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/48/3 page 7