Zeppelin Air Raid on Edinburgh 1916

Zeppelin Air Raid on Edinburgh 1916

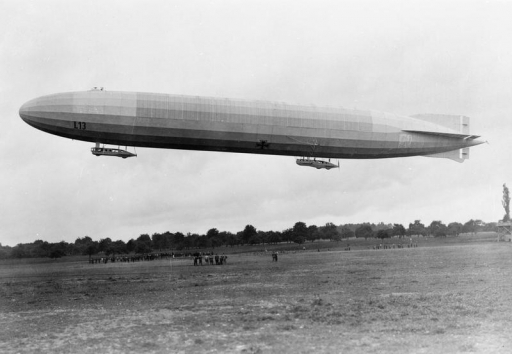

On the night of 2-3 April 1916 two German airships, the L14 and the L22, dropped 23 bombs on Leith and the City of Edinburgh. Reinhard Scheer had been appointed commander in chief of the German fleet at the end of February 1916 and, anxious to provoke the Royal Navy, he attacked the British mainland, using surface ships, submarines and airships in a combined operation. During the raid, thirteen people died and 24 were injured.

Zeppelin L13, sister-ship and identical to the Zeppelin L14, one of the airships which bombed Edinburgh in 1916.

Image used under Wikimedia Commons.

Warning of the impending air raid was received at 7pm on Sunday 2 April 1916, and the Police in Leith and the City of Edinburgh instituted air raid precautions: the Electric Light Department lowered all lights, traffic was stopped and lights on vehicles were extinguished. The Central Fire Station and the Red Cross were notified and all policemen, regular and specials, were called up.

The first reports of bombs exploding were received by the Police just before midnight. The L14, having crossed over the coast at St Abbs Head in Berwickshire on route for Rosyth and the Forth Railway Bridge, was unable to see its targets and dropped its bombs over Leith and the centre of Edinburgh. The L22 crossed over the mainland at Newcastle and dropped its bombs over the south of the city.

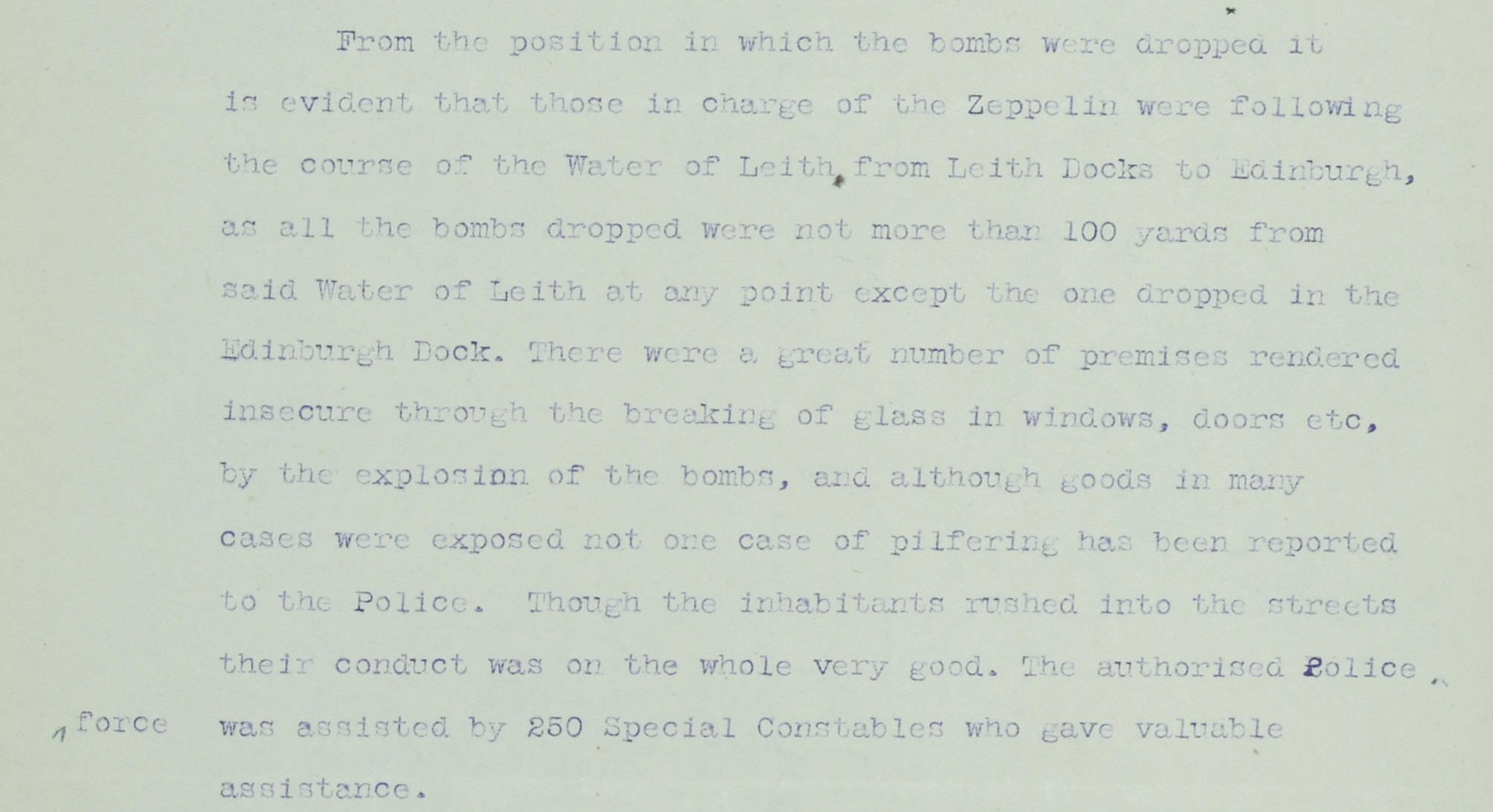

The Chief Constable of Leith noted in his report to the Under-Secretary for Scotland that ‘those in charge of the Zeppelin were following the course of the Water of Leith from Leith Docks to Edinburgh, as all the bombs dropped were not more than 100 yards from said Water of Leith at any point’ (National Records of Scotland, HH31/21/8 fol.17).

Extract from the report on the raid compiled by the Chief Constable of Leith, 1916,

National Records of Scotland, HH31/21/8 fol.17

The first few bombs landed in and around Leith Docks, damaging business premises and the quays and breaking a large number of windows in shops, offices and dwelling houses. Two bombs landed in Commercial Street, one killing Robert Love in bed in his top floor flat at no. 2 and the other falling through the roof of no. 14 ‘into a room occupied by an old woman and through the floor of her house into the house underneath where it burst into flame. The old woman referred to calmly got out of bed and poured water through the main hole made by the bomb and extinguished the fire.’ A further explosive bomb ‘fell on the roof of a whisky bond belonging to Innes & Grieve, wholesale spirit merchants, setting fire to the bond, which was entirely destroyed.’ Twenty bombs fell on Leith during the night, killing two people.

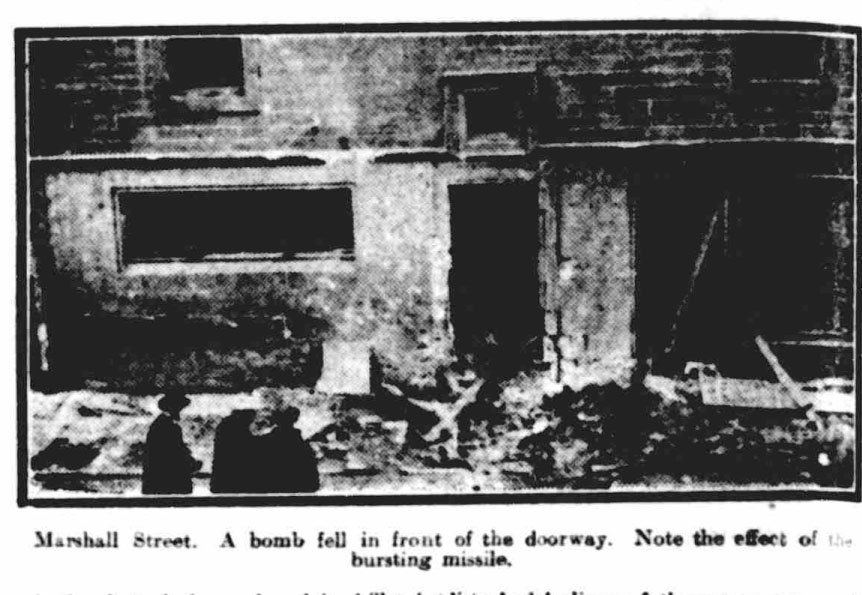

Peter McAusland, Detective Inspector in the Criminal Investigation Department of Edinburgh City Police compiled a detailed report of the bombs dropped on the City of Edinburgh, the number of people injured and killed, and the damage sustained to property. Seven incendiary and seventeen high explosive bombs were dropped on the city, many of them on the south side. This included a bomb which landed on the roadway approximately 400 yards from Edinburgh Castle and an explosive bomb which fell in the grounds of George Watson’s College, breaking a number of windows and damaging stonework on the steps. The White Hart Hotel in the Grassmarket and the County Hotel in Lothian Road suffered substantial damage, as well as a number of tenement buildings in Newington.

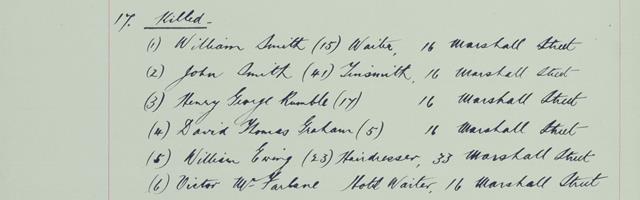

Several civilians were injured by broken glass or suffered shock, with two dying later from injuries sustained on the night. During the raid, seven residents of Edinburgh were killed, including five men at 16 Marshall Street in Newington. Private Thomas Donoghue of the 3/4th Battalion Royal Scots was visiting his family at 27 Marshall Street on the night of 2 April. He received severe injuries to his abdomen from a fragment of shell and died eight days later from peritonitis and heart failure.

List of those killed at 16 Marshall Street and 33 Marshall Street,

National Records of Scotland, HH31/21/8 fol.39

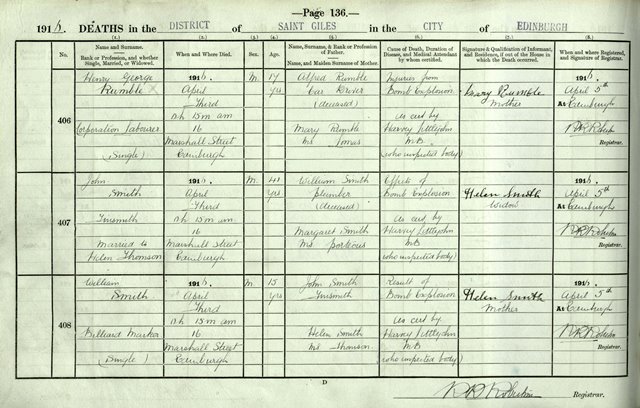

Entries in the Register of Deaths for three of those who died at 16 Marshall Street, 1916, National Records of Scotland, 685/4 p.136

Damage to 16 Marshall Street, from an article published in The Sunday Post, 9 February 1919.

Reproduced by kind permission of The Sunday Post (c) DC Thomson & Co Ltd

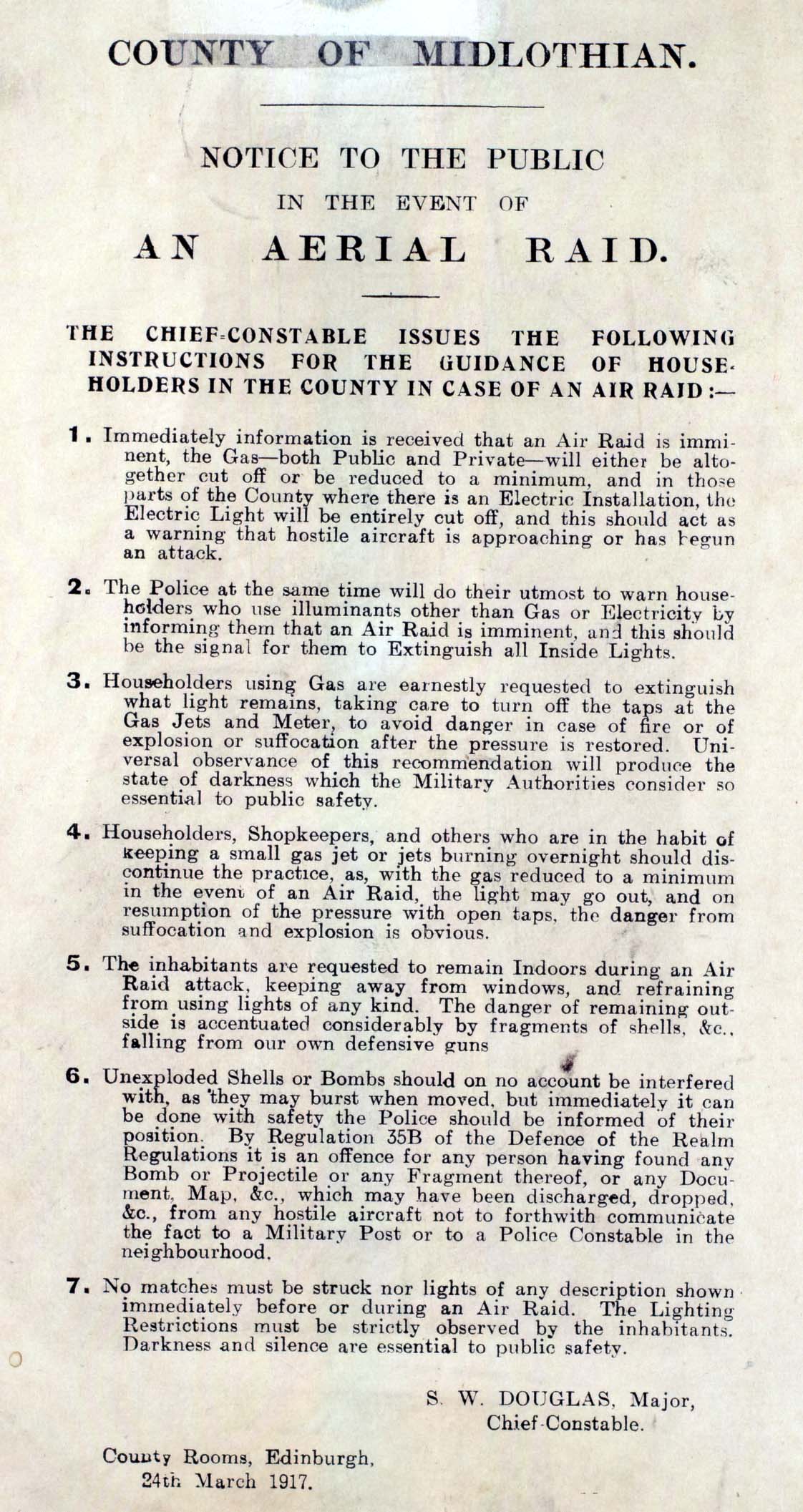

Following the raid, the Chief Constable of Leith queried whether the current air raid precautions were sufficient, drawing attention to air raid precautions which were only concerned with electric light and ignored gas light, and to the large number of vessels lying in Leith Roads every night which ‘are fully lighted and the glare in the sky on a dark night can be seen at a long distance. A better guide for a Zeppelin could not be got. On the night of the Raid the Zeppelin came to Leith across the line of the shipping and not till the bombs were falling on Leith were the lights on the ships extinguished. It seems so ridiculous to have the town of Leith in darkness while the sea in front is illuminated.’ (National Records of Scotland, HH31/21/8 fols. 23-26) A reply to the Chief Constable dated 10 April 1916 confirmed that the Admiralty ‘orders that no lights of any description visible from outboard will be permitted in mercantile shipping anchored in the Leith and Granton roadsteads.’ (National Records of Scotland, HH31/21/8 fol.69) A notice published by the Chief Constable of Midlothian in March 1917 shows that air raid precautions had been amended to take account of both gas and electric light (National Records of Scotland, GD18/6182).

Guidance for the public in the event of an air raid issued 24 March 1917, National Records of Scotland, GD18/6182.

Reproduced by kind permission of Sir Robert Clerk of Penicuik.

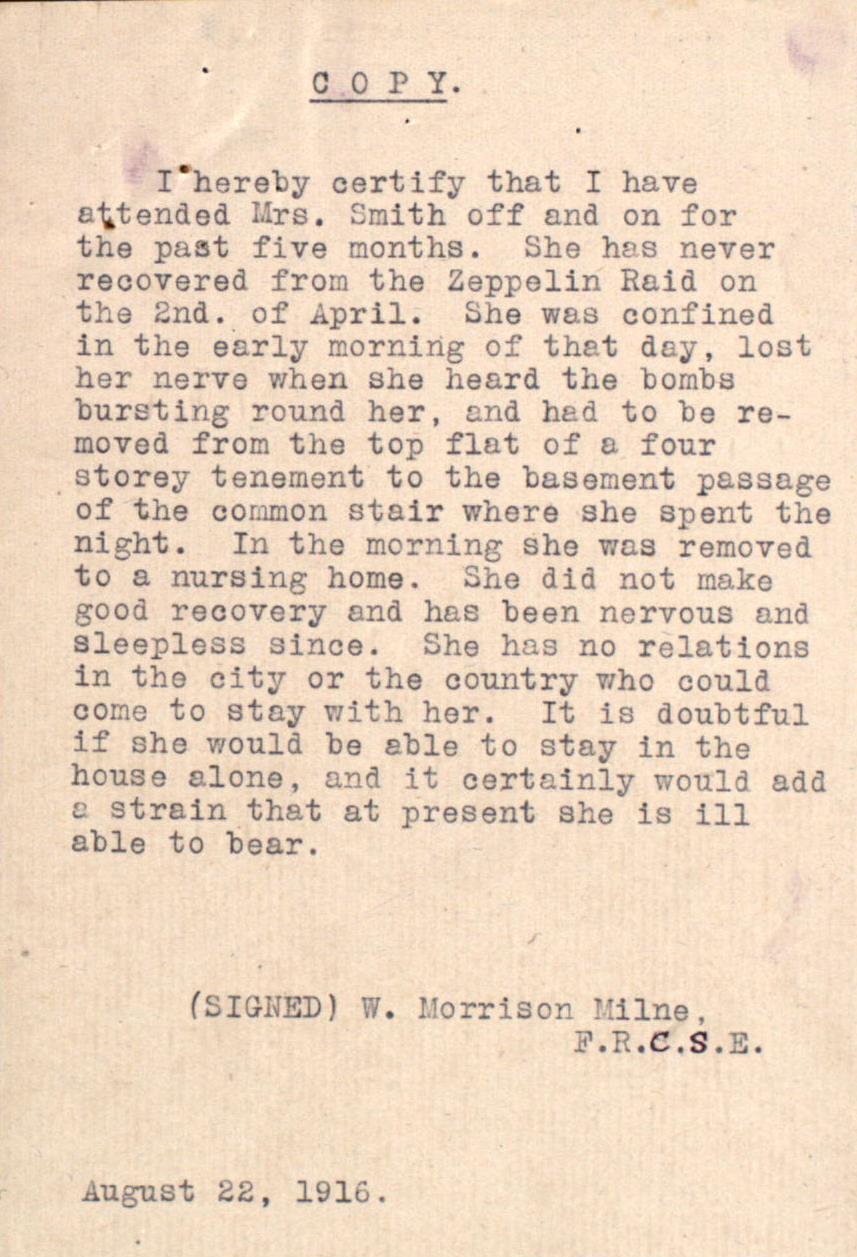

Beyond the immediate deaths and injuries sustained during the air raid, some Edinburgh residents continued to suffer from the shock and stress for some months after the event. An appeal to the Military Service Appeal Tribunal on behalf of Peter Smith, a teacher, pleaded the continuing ill health of his wife since the Zeppelin air raid on 2 April. Mrs Smith had safely given birth to a baby daughter in the early hours of 2 April but had lost her nerve during the raid a few hours later, having to be moved from the top flat of the four storey tenement to the basement passage of the common stair where she spent the night. When the baby’s birth was registered, she was named Catherine O’May Campbell Raida Smith – ‘Raida’ does not appear to be a family name and may perhaps reflect the child’s earliest experiences.

Evidence presented to the Military Service Appeal Tribunal in support of Peter Smith's appeal, 1916,

National Records of Scotland, HH30/7/5/27/4

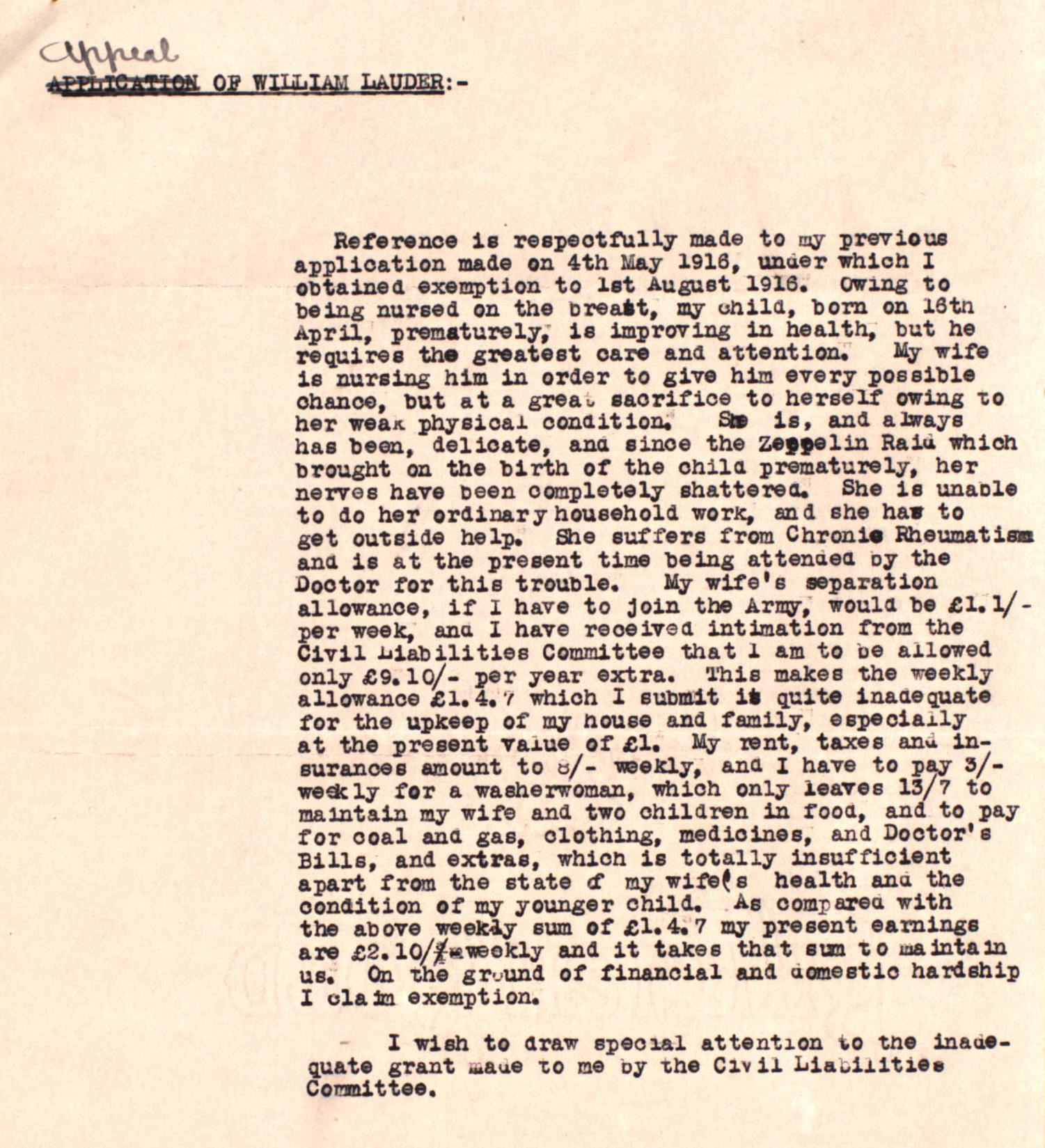

A similar appeal was made on behalf of William Lauder in October 1916. His wife was pregnant and the shock and stress of the air raid brought on the premature birth of their son, William Youngson Lauder on the 16 April 1916. William pleaded the needs of the premature baby and his wife’s chronic rheumatism in support of his appeal to the Military Service Appeal Tribunal.

Evidence presented to the Military Service Appeal Tribunal in support of William Lauder's appeal, 1916,

National Records of Scotland, HH30/8/1/10/5

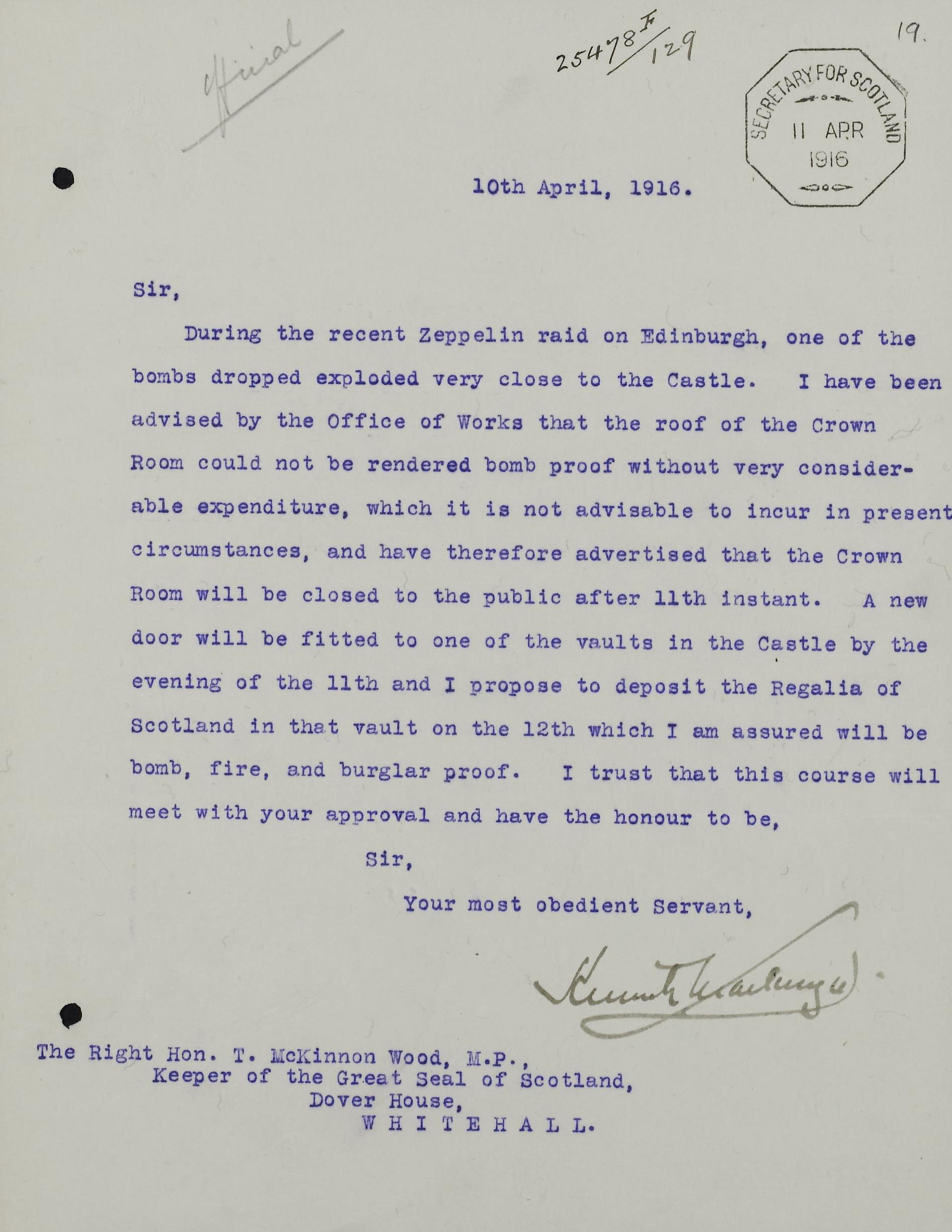

Following the Zeppelin raid, additional precautions were taken to protect the Regalia of Scotland. These were removed from the Crown Room in Edinburgh Castle to one of the castle vaults to ensure their safety.

Letter to the Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland regarding a place of safety in which to store the Scottish Regalia, 1916,

National Records of Scotland, HH31/21/1 fol.19

Storage in the vaults was a temporary measure. In 1918, Kenneth Mackenzie wrote again to the Secretary for Scotland that ‘in view of the risk of bombs from Zeppelins I deemed it necessary to close the Crown Room at Edinburgh Castle and place the Regalia of Scotland in a place of absolute safety. There does not now appear to be much further risk of damage from this cause, and in view of the large number of Colonial officers and men who are constantly on leave in Edinburgh, in addition to our American Allies, it appears desirable to exhibit the Regalia so that they can have the opportunity of viewing them during their stay in Scotland.’ (National Records of Scotland, HH31/21/1 fol.9)

To find out more about Government files and Military Service Appeal Tribunals in our collection, read our research guides .