A Victorian Valentine

A Victorian Valentine

A Valentine's card became the poignant symbol of broken promises rather than a token of love when it was produced as evidence in a 19th century court case.

In 1879, Mary Ann Lindsay began working in the shop of William Steel, wine and spirit merchant in Johnstone, Renfrewshire. It wasn't long before she caught the eye of her employer's son, William Steel junior, a student at Glasgow University, where he was studying for the ministry. According to the Sheriff Court papers, William "repeatedly took [Mary Ann] out walking and paid his addresses to her as if in honourable courtship with a view to marriage, and did all he could to insinuate himself into the affection of [Mary Ann], for whom he professed the warmest love" (National Records of Scotland, SC58/22/630).

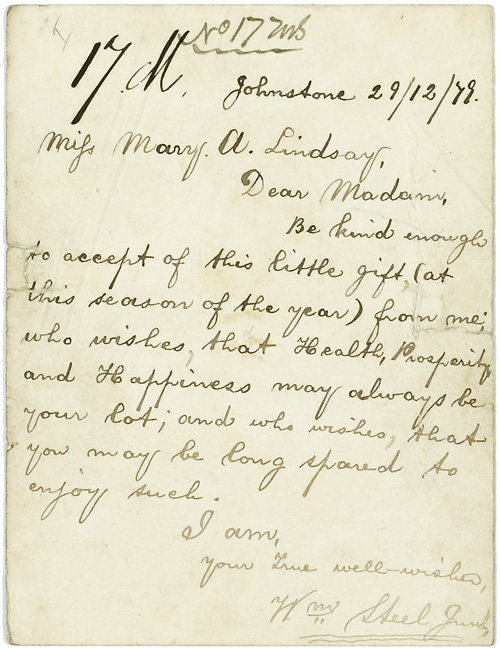

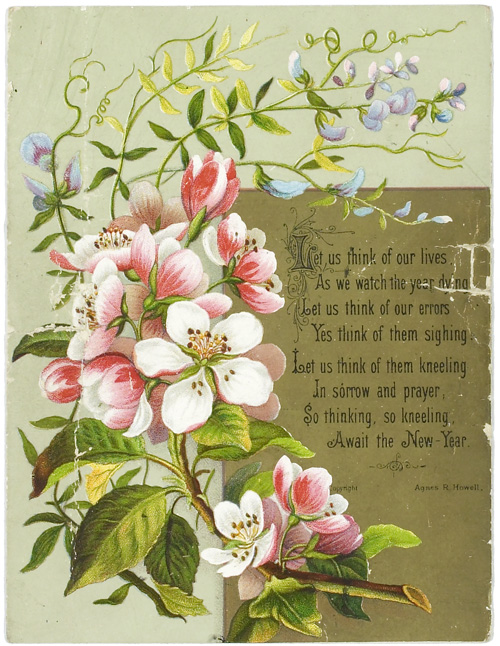

Valentine's card, 1880

National Records of Scotland, SC58/22/630

In January 1880, Mary Ann discovered that she was pregnant. At first, William appears to have accepted that the child was his and promised financial support if Mary Ann would "keep the matter quiet", but by the time little Ann Lindsay was born in Johnstone on 27 October 1880, the relationship had turned sour.

On 7 December 1880 Mary Ann and her father, David Lindsay, a mason, raised an action against William in Paisley Sheriff Court. They claimed that Mary Ann, by now 19 years old, was entitled to lying-in expenses and aliment as well as compensation because William, also 19, had seduced her by promising marriage.

William claimed that he had only walked out with Mary Ann twice, after a quarrel with his girlfriend Agnes Braidwood. He denied admitting paternity and alleged that "during the time the pursuer was in the shop she did not conduct herself as an engaged person but on the contrary was over familiar with a number of young men".

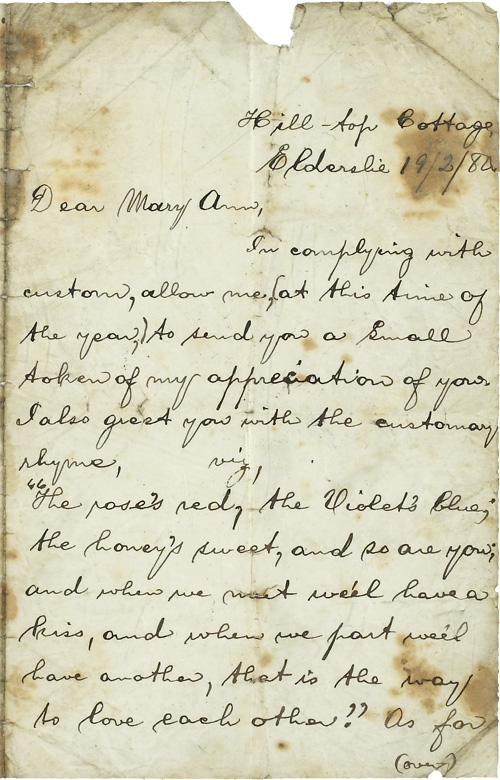

Letter from William to Mary, 19 February 1880

National Records of Scotland, SC58/22/630

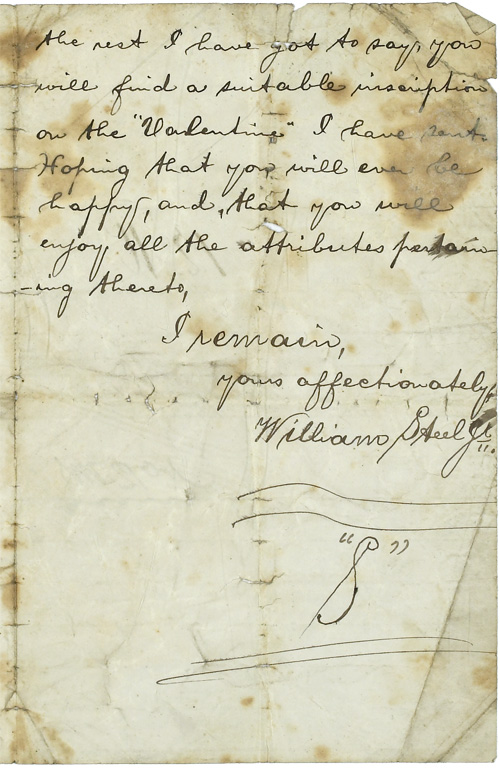

Mary Ann claimed that she told William's father about the pregnancy in the spring of 1880. It appears she lost her job at around the same time. She produced correspondence from William to back up her claims - including a festive note from December 1879 and the valentine card. Along with the Valentine, William had written a note including the verse:

"The rose's red, the Violet's blue,

the honey's sweet, and so are you,

and when we meet we'll have a kiss,

and when we part we'll have another,

that is the way to love each other."

Festive note, 29 December 1879

National Records of Scotland, SC58/22/630

The fathers met to resolve matters, but their accounts of what passed between them differ. David Lindsay had wanted Mary Ann and William to get married, but William's father proposed that Mary Ann should be sent away until the baby was born, after which she would get her job back. David Lindsay's brother in law, Joseph Fields, who accompanied him to the meeting, claimed that William Steel senior had said that his son "was a poor useless thing on whose education he had spent £500" and that he could not support a wife. William Steel senior, on the other hand, denied this version of events and claimed that his son never admitted to him that he was the father of little Ann.

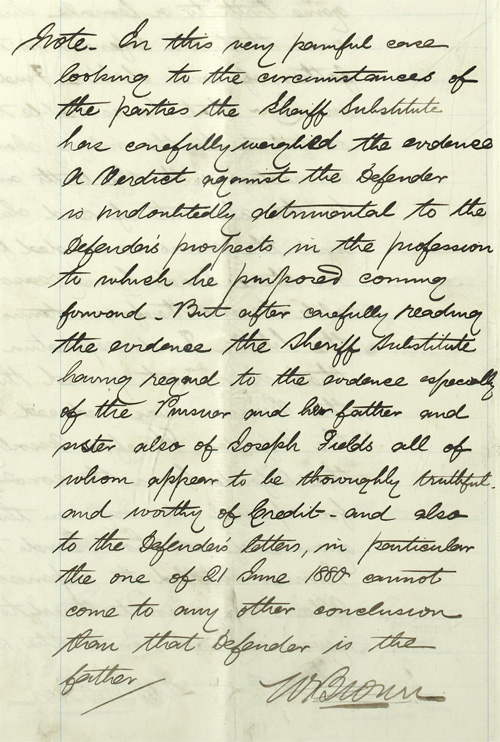

Detail of Interlocutor sheets, 19 July 1881

National Records of Scotland, SC58/22/630

On 19 July 1881 the Sheriff Substitute found against William. In his summing up of the "very painful case" he acknowledged that a verdict against William would be "detrimental to the defender's prospects in the profession to which he purposed coming forward [but] cannot come to any other conclusion than that the defender is the father of the pursuer's child". He awarded Mary Ann court expenses and the money she had claimed for the birth and maintenance of the child, but did not find sufficient evidence to support her claim for damages for seduction.

William appealed to the Court of Session but the Sheriff Substitute's verdict was upheld and Mary Ann Lindsay was again awarded court expenses. William Steel was ordered to pay Mary Ann a total of fifty-five pounds, six shillings and one pence and was named as Ann's father in the Register of Corrected Entries.

Thousands of single mothers like Mary Ann Lindsay took men to court to prove the paternity of their children, usually in an effort to extract financial support. Most of these affiliation and aliment cases were heard in the sheriff courts and can be found in the NRS catalogue under the names of the parties. Discover what other stories you can find in our Sheriff Court and Court of Session collections.