Hidden LGBT Histories

Hidden LGBT Histories

Badge from the 1970s. Image credit: www.gladtobegay.net

This February, the National Records of Scotland (NRS) is marking LGBT+ History Month Scotland, using our rich collection of archival material, to tell the forgotten stories of Scotland’s LGBT+ communities.

Sex between men was partially decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967, when the Sexual Offences Act came into effect. However, sex between consenting adult men remained illegal in Scotland for the next 13 years. Even following changes to the law in Scotland in 1980, Scotland’s LGBT+ communities continued to be subjected to discrimination and prejudice, forcing them to hide their sexuality from family, friends and work colleagues. Given the social stigma and legal status of same-sex relations, it is perhaps unsurprising that many voices remain unheard. To mark LGBT+ History Month Scotland 2021, we have explored the records of Outright Scotland, previously the Scottish Minorities Group (NRS, GD467), which gives a voice to LGBT+ communities of 1970s Scotland, at a time in which they faced significant legal restrictions and widespread social prejudice.

The Outright Scotland archive contains a rich trove of letters from across the country. These letters, often written by people located away from the main centres of population, stress how isolated individuals felt from their families and friends, and physically isolated from other members of the LGBT+ community. A large proportion of the correspondence was written in response to a documentary that had aired on BBC TV in December 1976 and made with the co-operation of the Scottish Minorities Group (SMG). The programme, Glad to be Gay? was part of the BBC’s Open Door series, produced by the broadcaster’s Community Programme Unit and focused on the day to-day running of the SMG which had its head office in Edinburgh, and the lives of the people who used its services. For many viewers from LGBT+ communities in Scotland, the programme was revelatory and was the first time they had seen people like themselves on mainstream TV: living ordinary lives, rather than being reduced to comic stereotypes, portrayed as tragic victims, or condemned as sexual deviants.

The SMG was founded in Glasgow in 1969 and moved to larger premises at 60 Broughton Street in Edinburgh in 1972. The SMG developed to become the Scottish Homosexual Rights Group (SHRG) and as Outright Scotland in a final incarnation in 1992. The organisation was active in campaigning for gay rights, providing counselling services and social gatherings all of which featured in the documentary. We are given a glimpse into the lives of some of the callers using the telephone counselling service and new recruits arriving at the Edinburgh branch. The programme is presented by Ian Dunn, founder of the SMG and Jean Malcolm from the Brook Advisory Centre, which gave and still gives advice to young people on sexual health and wellbeing. From reading some of the letters sent into the SMG after the airing of the programme, it seems many gay people were not aware of the existence of such organisations and many wrote to the SMG requesting membership details.

Outright Scotland logo, taken from 'Shout' newsletter, 1992. (NRS, GD467/2/1/5)

The authors predominantly lived in Scotland, but as the programme was shown across the UK, there were correspondents from England too, seeking advice on coming out, how to obtain gay publications and asking if there were similar organisations near them. The letters reveal a sense of isolation and often sadness that the opportunity to meet like-minded people and share their feelings was not available to them. One person wrote into the SMG after seeing Glad to be Gay?'I […] felt quite inspired by the programme. 'And added:

'I have been wanting to find out about such groups or contacts for some time but I have not known how to set about it.’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 11)

Another was struck by the programme’s depiction of homosexuals:

‘I realise that I am not the only isolated homosexual […] I was moved, especially by what seemed to be a deliberate attempt to present homosexuals as ordinary HUMAN beings’. (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 2)

Up until the 1970s, the mainstream media had represented the LGBT+ community by way of a limited number of stereotypes, focusing on gay men as overtly camp or effeminate. The diversity of LGBT+ lives was rarely represented on-screen. Notably missing are lesbians and the trans community. LGBT+ characters portrayed on TV were rarely truly ‘out’ or perceived in a positive light. Therefore, the representation of real gay and lesbian people in the Glad to be Gay?programme must have had a powerful effect on the LGBT+ viewers. One viewer wrote to the SMG:

‘..the complete absence of the “twee” types was a compulsive argument for the equality you are seeking, as inferred by one of your visitors who thought every homosexual had a limp wrist, […] this is how most of my friends regard gays.’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 19)

The theme of isolation frequents these letters, as their writers reach out for support from the group:

'I believe that the Scottish Minorities Group may provide besides an alleviation of my loneliness, the ability to converse with similar people…’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 16)

This person also addresses the anguish of coming out to his family:

‘I find it impossible to confide the sundry problems relating from homosexuality to my parents; such a disclosure would create total confusion; emotional upset. I would almost certainly be disowned from […] the family unit. This I wish to avoid at all costs!’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 16)

The letter is signed off:

‘Incidentally, since I live with my parents, would you please enclose your reply in an enveloped marked PERSONAL or CONFIDENTIAL’.

Here, as in many of the letters, the writer appears conflicted: there is an aspiration to be true to oneself and their sexual feelings, but faced with a potentially hostile reaction from family and friends and the ever looming possibility of arrest, many chose to hide their sexuality:

‘After seeing a Programme on television, (open door) approximately two-weeks ago, on gay people, it interested me tremendously, as i am in the same situation, + do have difficulty meeting people because of my gaiety, which realy get’s [sic] me down + makes me stay indoors, because i feel ashamed of being what i am’. (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 70)

This idea of concealment and secrecy is reflected in the title of the programme itself. The term Glad to be Gay may be familiar to us now as a gay anthem written by Tom Robinson. He performed the song live as part of a Gay Pride march in London in 1976 and also on ITVs So It Goesprogramme, in 1977, which can be seen in this YouTube video. The song, which was banned on Radio 1 at the time of its release in 1978, was in fact inspired by slogans Robinson had seen printed on badges, worn proudly by LGBT+ individuals while in the company of their peers, but removed and hidden when they returned home to ‘real life’. This duality is present in the correspondence, as the authors often ask for advice on coming out to family, work colleagues and even their churches.

There is also support for the SMG and their cause from Monklands District Council, congratulating the SMG on the television programme:

‘The content and style of the film should have done a great deal to assist your cause. Next. I am writing once again to let you know that I have made one more approach to the Lord Advocate asking when we might expect the law in Scotland relating to homosexuals to be put on a par with that in England.’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 62)

The SMG were perhaps hopeful that the programme may help the campaign to decriminalise homosexuality in Scotland. SMG’s reply to Monklands District Council was to further the cause for the age of consent of heterosexuals and homosexuals to be equal. This was something that would not be realised until 2000.

After the success of the programme, the SMG founder Ian Dunn wrote a letter to all Parliamentary members who voted on Clause 7 (Gross indecency between males) of the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 1976. The letter details the positive reaction of the viewing public, and in the six days following broadcast, the Edinburgh branch of the SMG received 90 calls and the Glasgow branch, 70. Dunn also notes that ‘18 letters were received in direct response to the programme.’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 15)

‘The majority of the telephone calls were from isolated people who were relieved to see a programme with which they could identify and find out about an organisation which expresses itself in a clear yet unaggressive way.’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 15)

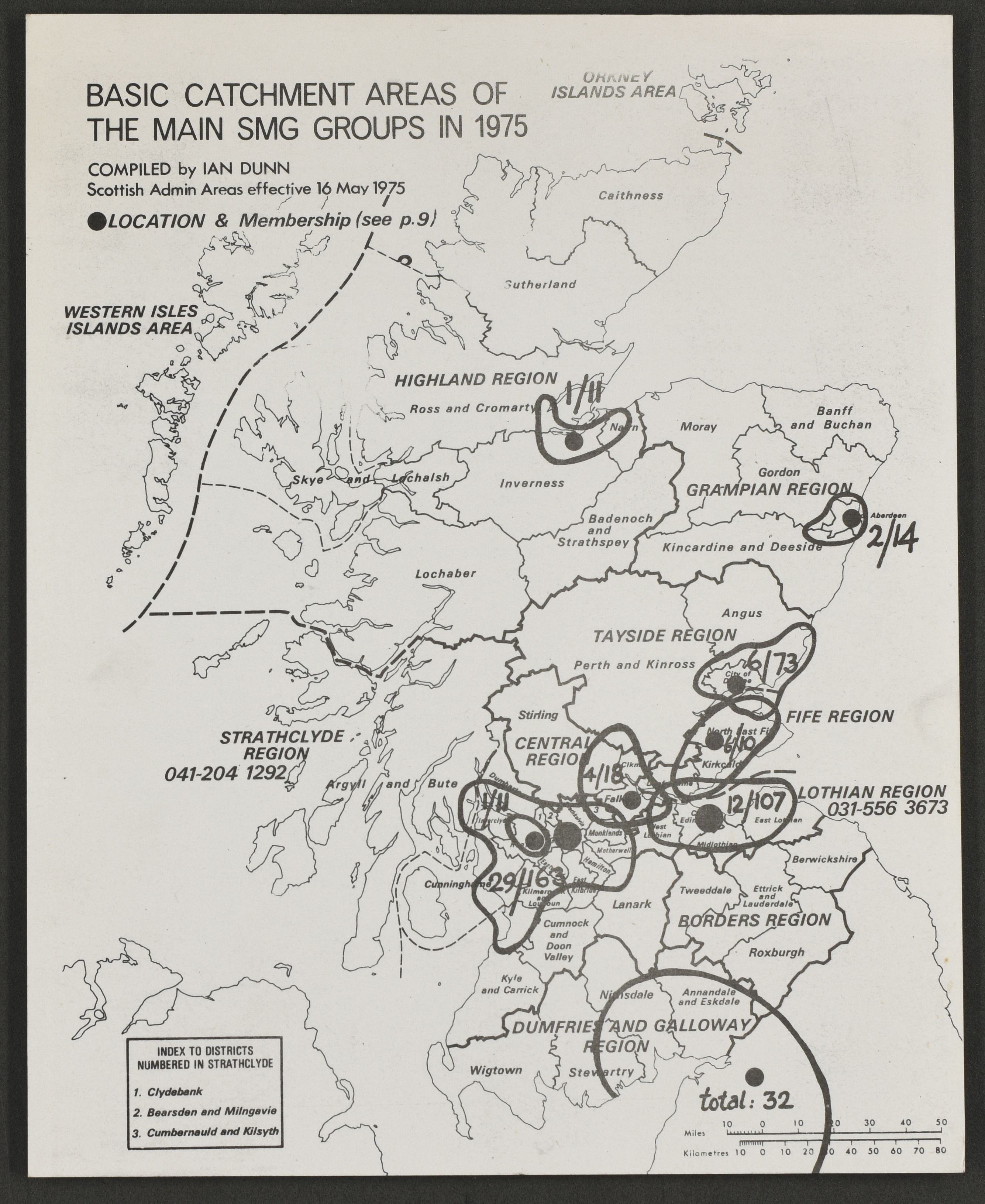

Membership numbers of the SMG across Scotland, a year before

‘Glad to be Gay?’ was broadcast. (NRS, GD467/2/4/8)

Such was the hostility endured by LGBT+ communities in Scotland for much of the twentieth century, that thousands entered into marriages of convenience to avoid losing their jobs or enduring awkward questions and social isolation. One such man wrote to the SMG after seeing the documentary:

‘I seen [sic] your programme on the BBC and I was very impressed. I would like too [sic] know if there is any where [sic] other than Edinburgh where I could go. I am 34 years old and I have a wife and three kids whom I love very much.’

‘I am not writing because I am out for kicks, I want it sincerely like too [sic] meet men and women like myself because it would put my mind at rest too [sic] know if what I have felt since I was in my teens is really what I want and not just kidding myself.’

He goes on to say he ‘felt quite inspired by the programme.’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27 page 11)

Among this extraordinary collection, one letter above all speaks of the impact the broadcast of Glad to be Gay?. Written nearly a year after the programme had been broadcast, the writer tells the SMG:

‘If your group had not produced its programme about homosexuals just over a year ago and managed to get it shown on television. I would not be alive today,’

They go on to say they had always known they were not heterosexual but ‘I was not like the type of persons portrayed in plays, films etc… who are supposed to represent homosexuals.’

‘I had never knowingly met a homosexual and at the age of 46 my life has become so empty it had lost all meaning – I had had enough. At this point I saw your programme on television + saw that there were homosexuals who were ‘normal’ + went to London + purchased a copy of Gay News, + with help of London ‘Friend’ + the Albany Trust am still alive. – I have still to live happily ever after’ – it is not easy starting life again at my age after being screwed up for so many years – but I now associate with many gay people + feel much more at ease in their company + take an active interest in the CHE [Campaign for Homosexual Equality] movement locally.

‘I feel very strongly that so much more needs to be done to help people who are gay to come to terms with themselves + society + that facilities for meeting each other in relaxed friendly surroundings are pathetically inadequate.’

‘Please keep up the good work + pass on my thanks to all of those who stick their necks out + appeared in the programme + particularly to the lad in Fort William (I think) – this had a great effect on me + helped me to ‘come out’ at work last week – it would have been easy to have put it off a bit longer – but then if your chaps had delayed for another month this letter would not have been written… [sic]’ (NRS, GD467/1/2/27page 91)

These letters give a voice to many LGBT+ people who felt they had to conceal their sexuality due to the prevailing social attitudes of the day. Much has changed since the first broadcast of Glad to be Gay? in 1976. Other important changes in law which effect LGBTI+ population are the Civil Partnership Act in 2004, followed by the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014. These landmark changes are due in considerable part to the hard work and activism of LGBT+ alliances, past and present.

Front cover of SMG Gayzette from July 1976. (NRS, GD467/1/3/12)

The letters cited in this article have been digitised in redacted form. The personal details of all correspondents have been removed under Data Protection laws.

Resources used

National Records of Scotland, Outright Scotland archives (GD467)

LGBT History Month Scotland, LGBT History Month Scotland 2021

Open Door – The Scottish Minorities Group – Glad to be Gay? BBC Archive

The Guardian, How we made: Tom Robinson and Nick Mobbs on Glad to be Gay.

Glad to be Gay – Tom Robinson, Glad to be Gay