Scottish Soldiers at Waterloo

Scottish Soldiers at Waterloo

The equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington outside General Register House in Edinburgh gives the National Records of Scotland a unique link with the British general and his most famous victory at Waterloo on 18 June 1815.

The battle involved thousands of Scottish troops in the British army’s epic fight, alongside other allied forces, against Napoleon’s superior army. More than 4,000 British soldiers died in or soon after the battle, but the survivors earned the right to wear the Waterloo medal, and enjoyed the status of heroes at home.

The stories of some of the fallen and of the surviving veterans can be traced in documents held in the National Records of Scotland. The examples featured here mainly concern the 79th Regiment of Foot (Cameron Highlanders) and the 2nd Dragoon Guards (Scots Greys).

Quatre Bras 16 June 1815

Waterloo was preceded two days before by a very bloody encounter at a vital crossroads a few miles south of the more famous battlefield. British and allied units stopped the French advance northwards towards Brussels, but at a terrible price for the Scottish regiments fighting in the 5th Division, including the 79th (Cameron Highlanders), the 92nd Regiment (Gordon Highlanders) and the 42nd Regiment (Black Watch).

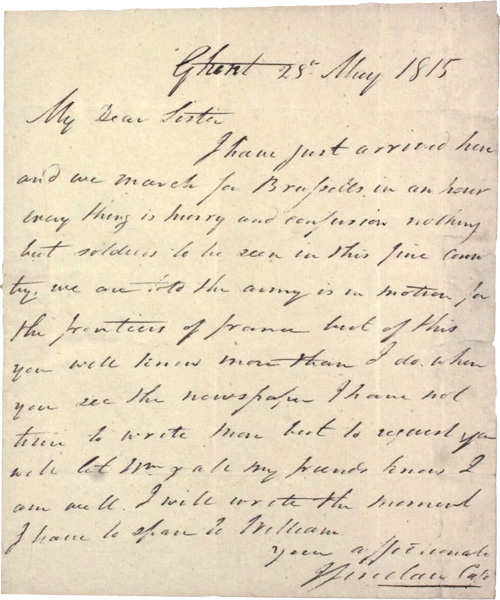

The Cameron Highlanders threw back a French infantry attack at bayonet point, but took heavy casualties from artillery fire and cavalry attacks. The battalion commander, 14 other officers, 12 sergeants and about 250 other ranks were wounded at Quatre Bras. Some 25 rank and file were killed, and one of the two officers to die was Captain John Sinclair from Caithness, commanding No. 4 company. A veteran of the Peninsular campaign, Sinclair reported on military preparations in one of his last letters home to his sister Bettsy on 28 May, written in haste as the regiment marched to Brussels.

Letter from Captain John Sinclair, 28 May 1815,

National Records of Scotland, GD139/369/28

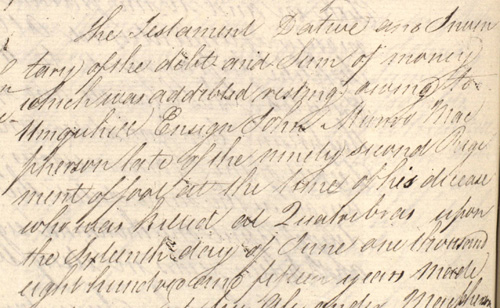

The Gordon Highlanders also suffered badly, losing among many others, their commanding officer and an ensign, John Munro McPherson. He died without having made a will, and the inventory of his estate reveals that two years later his surviving brother and sister in Edinburgh were anxious to benefit from the sum of £2 sterling, the portion of the prize money owing to him for his services in the field.

Testament of John Munro McPherson,

National Records of Scotland, CC8/8/143

Transcription of Testament CC8/8/143

Waterloo 18 June 1815

The 1st Brigade of the British 5th Division was drawn up east of the main Brussels to Charleroi road, with the Cameron Highlanders at the centre of the brigade position. Its experiences during the battle were in some ways typical of the British units, which withstood very heavy bombardment by the French artillery and repeated attacks by infantry and cavalry. Along with the Gordon Highlanders they famously repelled an attack by the numerically superior columns of d'Erlon's corps. Their counter-attack was followed by the charge of the Union Brigade of dragoon regiments, including the Scots Greys, which devastated the French columns. The 79th Highlanders suffered from cannon fire throughout the day, and formed one of the unbreakable squares against numerous attacks by the French cavalry. At the end of the battle, the shattered remnant of the 79th Highlanders was commanded by a Lieutenant, Alexander Cameron, as all senior officers were dead or wounded.

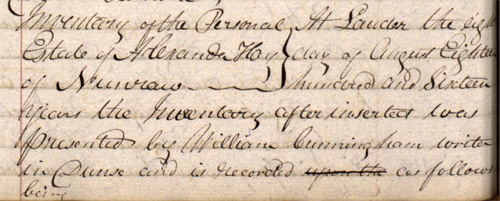

Among British cavalry casualties on 18 June was a young laird, Alexander Hay of Nunraw, who served as an ensign in the 16th Regiment of Light Dragoons that covered the retreat of the Scots Greys. Born 6 September 1796, Hay was just nineteen years old when he was 'killed in the field of Watterloo'. He died intestate, but the inventory of his estate provides a snapshot of the wealth of the proprietor of a small East Lothian estate.

Inventory of Alexander Hay, National Records of Scotland CC15/7/2

Transcription of Inventory CC15/7/2

Waterloo veterans

Most Scots who left the army after the service in the Napoleonic Wars went home to where they were born or had lived and worked before they enlisted. Not all found work in the post-war economic slump, but apart from labouring, a common occupation was weaving, and soldiers also became shoemakers and tailors. Others went into the service of civil authorities, as police officers, sheriff officers and jailers.

The high standing of the Waterloo veterans, and the link they provided to the historic battle, meant that the deaths of respected individual veterans were noticed in local newspapers as the decades passed. Featured here are survivors of Waterloo from the Cameron Highlanders and the Scots Greys.

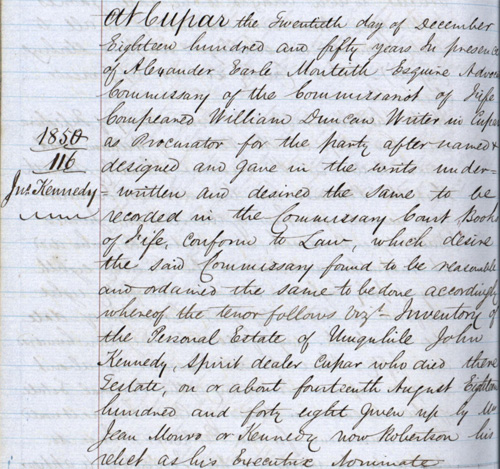

John Kennedy, Sergeant, 79th Regiment of Foot

He was born in 1786 in Renfrew, joined the army in 1804, and fought at Waterloo as a veteran of the Peninsular War and other European campaigns. After his discharge Kennedy served for fourteen years as keeper of the county jail at Cupar, Fife. He was also a sheriff officer, and in 1837 was involved in policing an election riot in Auchtermuchty. Later he became an inn keeper in Cupar. His military training and experience probably helped in all these occupations. He was a staff sergeant of the pensioners corps. On anniversaries of Waterloo he fired 'several discharges of cannon' from the Moathill in Cupar. He died at Cupar on 14 August 1848, in his 62nd year. In 1846 he made a will jointly with his wife, Jean Munro, who remarried in January 1849. The inventory of his estate lists the household furniture and other possessions, amounting to £34, that she inherited.

Inventory of John Kennedy, National Records of Scotland, SC20/50/21

Transcription of Inventory, SC20/50/21

John Dunn, Private, 79th Regiment of Foot

Dunn was born in the parish of St Quivox near Ayr. He worked as a labourer while serving in the Ayr militia. In 1807 he enlisted in the army at the age of twenty-four. he fought at Quatre Bras, and at Waterloo where, his obituary stated, he acted as bugler to Sir Neil Douglas, commanding officer of the 79th. He was wounded by musket balls. His discharge papers stated he was 'severely wounded in the testicles and right groin'. Dunn recovered and continued to serve in the regiment in France until 1818. During its posting at Limerick in 1821, Dunn was discharged, for 'impaired constitution from irregular living'; the medical officer stated he suffered from rheumatism and asthma.

He became a weaver in Ayrshire and Stirling. He named a daughter Montague Maule Dunn in compliment to one of the regimental officers, Lieutenant Fox Maule and his wife Montagu Abercromby. Maule became an MP, was twice Secretary of State for War and as Earl of Dalhousie offered to support Dunn's claim for increased pension in 1864. Dunn died on 12 April 1872, aged 87. In his obituary he was described as 'a most intelligent and steady old man'. ('Glasgow Herald', 15 April 1872).

James Mason, 79th Regiment of Foot

Mason was also said in an obituary notice to have served as a bugler to Sir Neil Douglas at Waterloo, but he is not in the standard lists of the veterans. Born around 1795, at the end of his life he was living in the Lawnmarket, Edinburgh. He died on 15 October 1844, aged 50, from a 'disease of the chest' according to the register of burials. Only the day before he had attended a parade of the veteran corps of pensioners, at which he spoke to his former commanding officer, Major General Sir Neil Douglas (Governor of Edinburgh Castle and Commander-in-Chief of forces in Scotland). For the veteran's funeral on 21 October the corps of pensioners formed up outside his house, with band and firing party. The men then marched with the coffin held shoulder high to the new cemetery at Warriston, where Mason was buried with military honours. Crowds gathered on the streets to watch, attracted by 'the novelty of the spectacle', according to the 'Caledonian Mercury' (21 October 1844).

Several veterans of Waterloo became innkeepers or kept boarding houses, including these two survivors from the Scots Greys.

Archibald Johnston, Sergeant Major, Scots Greys

Born in Lochmaben, Johnston joined the Scots Greys in 1800 at the age of seventeen. At Waterloo he was wounded in the hand, and severely injured when his horse fell under him. Discharged on a daily pension of 1 shilling and 11 pence, he became the landlord of the Waterloo Tavern in Dumfries, and later inn keeper of the Lamb & Flag, Dumfries, where annual Waterloo dinners were held. In his last years he was totally blind. After his death on 11 November 1847, the 'Dumfries and Galloway Standard' described him on 17 November as 'in every respect a fine specimen of a veteran British soldier'.

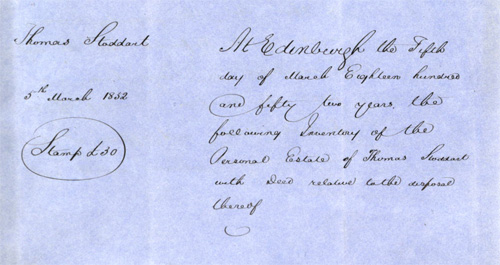

Thomas Stoddart, Sergeant, Scots Greys

Born in Newbattle around 1784, Stoddart served in Captain Poole's troop at Waterloo. He was keeping a boarding house in Causewayside, Edinburgh, at the time of his death on 8 February 1852. He died worth more than £1,000, and in his will he bequeathed money to his niece, Harriet Taylor, for 'the care and attention she has shown me, and the love and affection I bear to her'.

Inventory of Thomas Stoddart, National Records of Scotland, SC70/1/75

Transcription of Inventory, SC70/1/75

Transcription of Testament, SC70/4/70

You can find out more about the statue of Wellington in our feature, read up on Wills and Testaments in our guide and learn more about people linked to the battle on the ScotlandsPeople website.