Malicious Mischief? Women's Suffrage in Scotland

Malicious Mischief? Women's Suffrage in Scotland

2018 marked the centenary of the Representation of the People Act 1918, which granted some women the parliamentary vote. To celebrate, the National Records of Scotland (NRS) presented ‘Malicious Mischief? Women’s Suffrage in Scotland’, an archive exhibition reflecting on the actions of those who agitated for the vote: the suffragettes and suffragists. An online resource has been created from this exhibition which features: profiles for the women represented in NRS records; a timeline of women's suffrage; selected transcriptions from 1911 census returns; and images of the complete files relating to those women who championed the cause of women's suffrage. You can explore this online resource here.

Today we tend to associate the women’s suffrage campaign with the suffragettes – those women who used militant means to protest their lack of representation in government. Thanks to the public and press attention they received, these few years (1905-1914) have come to dominate much of the discourse on women’s suffrage. However, militant suffragism was actually relatively short-lived. The pursuit of female enfranchisement began long before, with the suffragists.

The Suffragists

Suffragists pursued the parliamentary vote through constitutional means such as peaceful protests, petitions and lobbying MPs to raise the issue in the House of Commons.

In 1832, the first petition on women’s suffrage was presented to Parliament by Henry Hunt MP on behalf of Mary Smith, a wealthy woman from Yorkshire. It was unsuccessful.

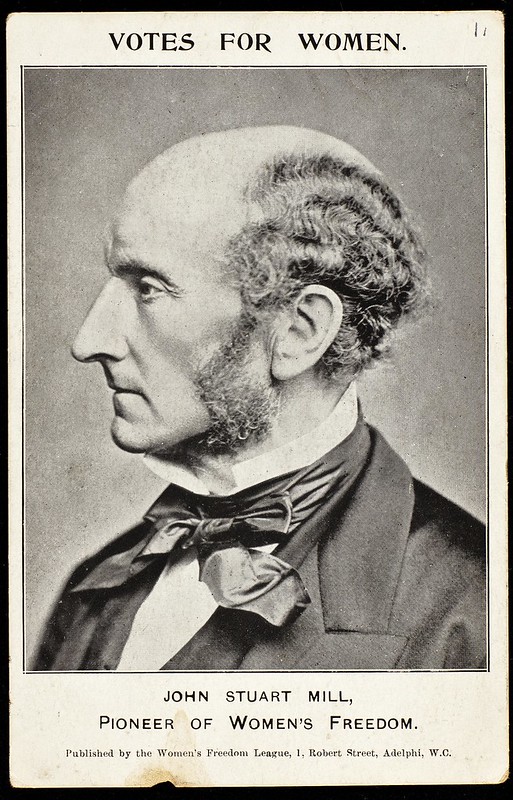

In 1866 a mass women’s suffrage petition bearing 1,521 signatures was presented to the House of Commons by John Stuart Mill. He proposed an amendment to the Second Reform Act 1867 to enfranchise all householders regardless of sex.

Postcard featuring John Stuart Mill, c. 1907 (The Women's Library at LSE)

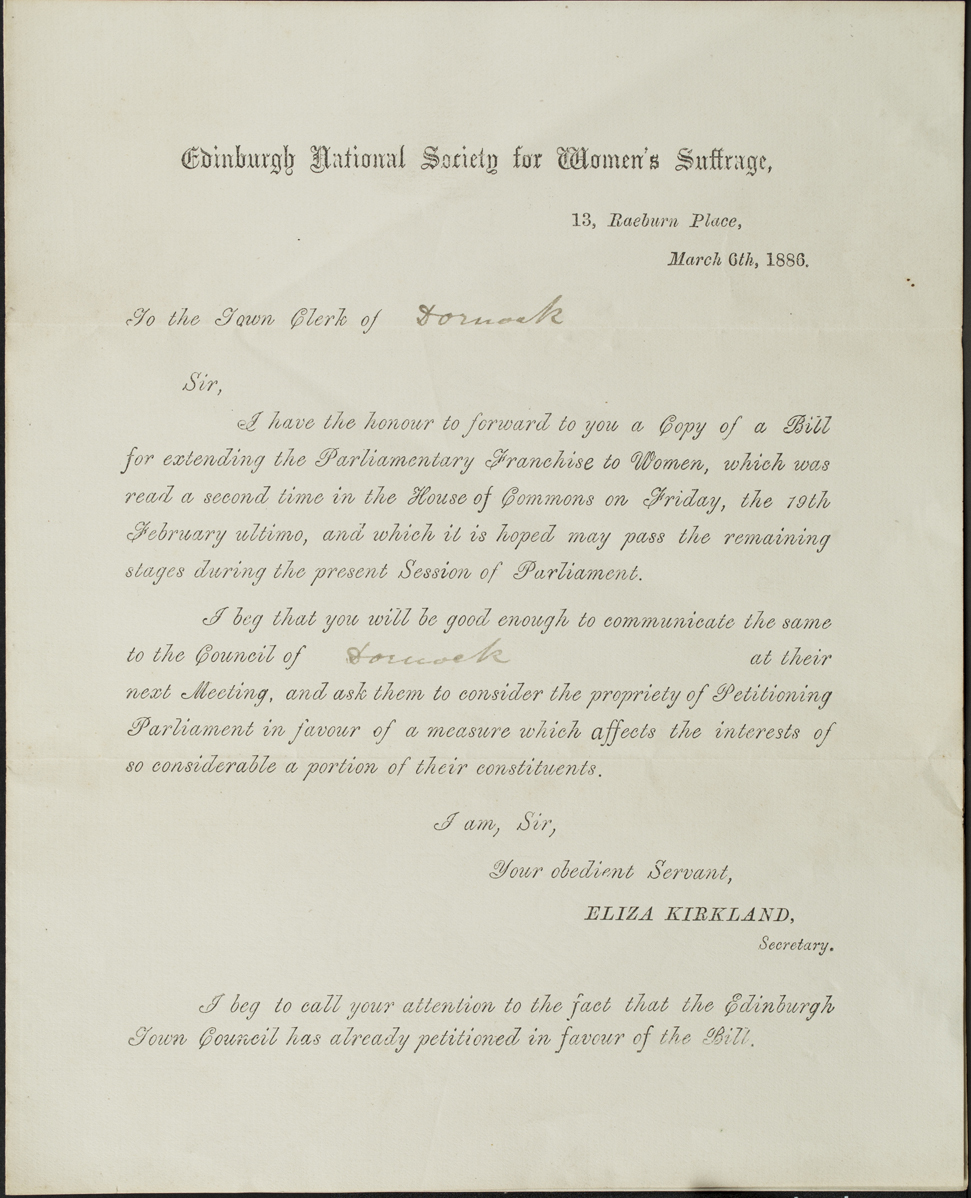

This was also unsuccessful, but proved to be the catalyst for organised campaigning. At this time the first women’s suffrage society in Edinburgh, the Edinburgh National Society for Women’s Suffrage (ENSWS), was constituted and began to campaign in earnest.

Circular letter from Edinburgh National Society for Women’s Suffrage. These circulars sought to solicit support for a bill extending the parliamentary franchise to women, 6 March 1886. Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, B15/6 p27

Between 1870 and 1884 a debate on women’s suffrage took place almost every year in parliament, and the movement grew as more women committed to the cause.

National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies

Organisations proliferated across Britain to pursue the parliamentary vote on the same terms as men. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed to coordinate their efforts. Millicent Fawcett served on the executive committee and became its president in 1907. The NUWSS gathered together regional societies with no political party allegiance and that used peaceful tactics to work towards the vote .

Lady Frances Balfour (née Campbell) by Bassano Ltd whole-plate glass negative, 20 November 1919 (NPG x19246, © National Portrait Gallery, London)

The leading suffragist, Lady Frances Balfour (1858-1931) worked for the Women’s Liberal Unionist Association in the late 1880s and became a leader of constitutional suffragists. She served on the executive committee of NUWSS from its formation in 1897 alongside Millicent Fawcett. Balfour’s aristocratic background makes her participation in suffragism unusual, but with a politically-active Liberal family, she was prepared to be ostracised for the cause. Balfour wrote, marched and spoke on women’s suffrage throughout Scotland and England.

Balfour’s letters, held by NRS, reveal her participation in the peaceful NUWSS United Procession of Women of 1907 - commonly known as the ‘Mud March’ - in which 40 suffragist societies and over 3,000 women marched from Hyde Park to Exeter Hall, London. It also reveals her perception of both peaceful and militant protests, and the actions of the Government in response. Although many suffragists were outspoken in their disapproval of militancy, suffragists and suffragettes often collaborated. She expressed her mixed feelings: “I don’t know whether I like the policy, but I do admire the courage & resource of the women” (National Records of Scotland, GD433/2/337 32 ).

The NUWSS 1907 procession was the first of several during the campaign and was a form of protest that advertised the number of women agitating for the vote. Another well-known event of passive agitation was the boycott of the 1911 census.

"If women don't count, neither shall they be counted"

Organised by the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), the boycott was a form of civil disobedience and passive militancy. Believing that taxation without representation was a form of tyranny, the WFL encouraged all suffrage societies to participate in the boycott through evasion - avoiding the notice of the enumerator - or resistance - refusing to provide information.

The 1911 Scottish census reveals precious evidence of the boycott. The enumerator noted individuals who refused to provide information as ‘Suffrage Protestors’. One other notable record includes a returned census schedule with ‘no votes for women, no information from women’ written at the top.

Photograph of suffragettes, Edinburgh, on census night, 1911 (Image used by permission of the Trustees of the National Library of Scotland)

The nature of the boycott means we do not know exactly how many women participated. However, the success of the boycott lay more in the press attention it received. Delighted with the suffragists' actions the press published extensive details on why women were refusing to be counted and the entertainment they organised for the occasion. This captured the public’s imagination and further advertised the suffragists’ aims.

Suffragists had been campaigning for several decades, and Acts were passed which gave more rights to women in local elections, but in 1903 a new form of agitation was to come to the fore. Fed up with the slow progress, Suffragettes were set to re-invigorate the movement.

The Suffragettes

Deeds not Words

First used in the Daily Mail in 1906, ‘suffragette’ was a deliberately negative name given to those suffragists who, impatient with the Government’s continued indifference to peaceful protests, had decided to take militant action. Coined as a term of derision, the name was quickly appropriated as a badge of identity, distinguishing them from their suffragist sisters.

The first militant action occurred in Manchester on the 13 October 1905 when the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) interrupted a Liberal political meeting by putting questions to the speaker on women’s suffrage. Physically ejected from the meeting, one of the group, Christabel Pankurst, spat in the face of a policeman and was arrested, gaining considerable publicity for the cause.

Although merely asking a question at a public meeting may not seem shocking today, in the 1900s, by being present at this meeting these women were breaking societal norms. A political meeting was seen as a public, masculine space, and women were expected to remain confined to their ‘domain’ of the private and domestic. By being physically present, demanding admittance, and daring to make themselves heard, these women shocked the public and those present at the meeting; who, unable to tolerate a woman asking a question in public, physically ejected them.

Women’s suffrage was intrinsically linked to an on-going debate surrounding the role of women in society, from the beginning of the campaign for women’s suffrage in 1837 and across the period when the suffragettes were active (1905-1914). Known as ‘the woman question’, this debate looked at women’s contribution to the nation, and covered not only their marriage and property rights, but their reproductive rights. These issues still persist and are continually revisited today.

During this time, women were charged with the production and care of the race , and were expected to serve the needs of their families and society with no recompense. The notion that women might wish to step out of the private domestic sphere into politics, went against the accepted cultural norms of the time.

This perception and portrayal of gendered characteristics was used not only by anti-suffragists, but by suffragists and suffragettes. All argued that women’s maternal and feminine influence should be brought to bear on the welfare of women and children, the improvement of social welfare, and the protection of the race’s wellbeing and morality. They simply disagreed on how this influence could best be wielded.

Malicious Mischief?

Suffragettes in Scotland: Ethel Moorhead

NRS holds a wealth of records about suffragette activities in Scotland, including their prosecution, imprisonment, newspaper reports and cases of force-feeding.

Illustration of Ethel Moorhead from the magazine, The Wizard of the North (no.401, March 1912, p.7).

Courtesy of Libraries, Leisure and Culture Dundee

One of the most infamous Suffragettes in Scotland was Ethel Moorhead – alias Edith Johnston, Mary Humphreys or Margaret Morrison. Moorhead repeatedly made the papers through outrageous militant acts. This led her to be dubbed the Scottish leader of the suffragettes, despite no such position existing. Convicted a total of five times, Moorhead’s antics allowed ample opportunities to advertise women’s suffrage as the arrest, prosecution, release and re-arrest were followed by the press.

Newspaper cutting from an unidentified newspaped, undated. Features a photograph of Ethel Moorhead, alias 'Miss Morrison' (in the middle), and Dorothea Smith (far right). Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH16/40

On 15 October 1913, Moorhead and Dorothea Chalmers Smith or Lynas were convicted of house-breaking and attempted fire-raising and sentenced to eight months’ imprisonment. Both immediately went on hunger strike and were released under the controversial ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ after five days fasting. Once she recovered Moorhead disappeared but was re-arrested in February 1914. Committed to Calton Gaol, Edinburgh, she became the first suffragette to be force-fed in Scotland.

By force or 'artifical' feeding

While England had resorted to force-feeding in 1909, it was widely believed that Scotland would not adopt this measure. In reality Scottish authorities had been discussing the possibility of force-feeding as early as 1909 but due to a number of circumstances it was not carried out until 1914.

Dr James Devon was appointed as Scottish Prisoner Commissioner on 31 March 1913 and was widely credited as having introduced force-feeding to Scotland. Indeed, his notes reveal that he wanted the suffragettes to consider him responsible. Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH12/78/9

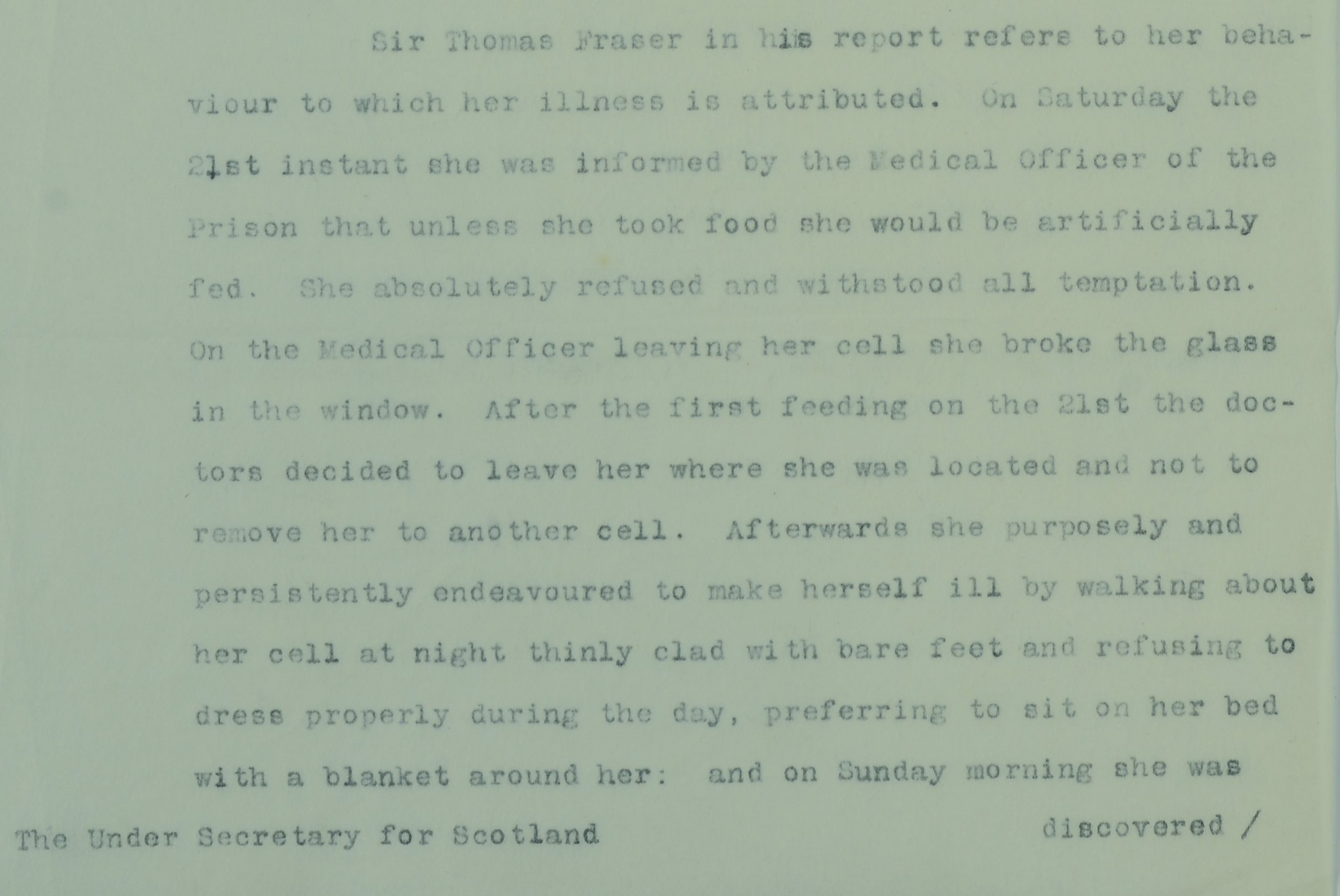

No suffragettes served their full prison sentence when hunger-striking and the authorities were left in the embarrassing position of being unable to retain their prisoners. Force-feeding was adopted in an attempt to keep suffragette prisoners healthy enough to serve the duration of their sentence, but it was ineffective. Moorhead was force-fed for only four days before being released with double pneumonia.

According to press reports and official memos, doctor Grace Cadell attributed this diagnosis to food entering her lungs through improper feeding. However, the medical officer responsible, Dr Ferguson Watson, furiously denied this. He claimed that Moorhead subjected herself to the possibility of ‘getting a chill’ by smashing her cell windows and being inappropriately dressed.

Part of a copy letter from Dr James Devon to the Under Secretary for Scotland, 26 February 1914, regarding the treatment of Ethel Moorhead, alias Margaret Morrison. Crown copyright, National Records of Scoland, HH16/40

The reaction of suffrage campaigners, those sympathetic to the cause, as well as press reports, reveal the outrage and disappointment at the actions of the authorities. This anger would be further stoked by the authorities’ treatment of Frances Gordon and Fanny Parker.

Frances Gordon

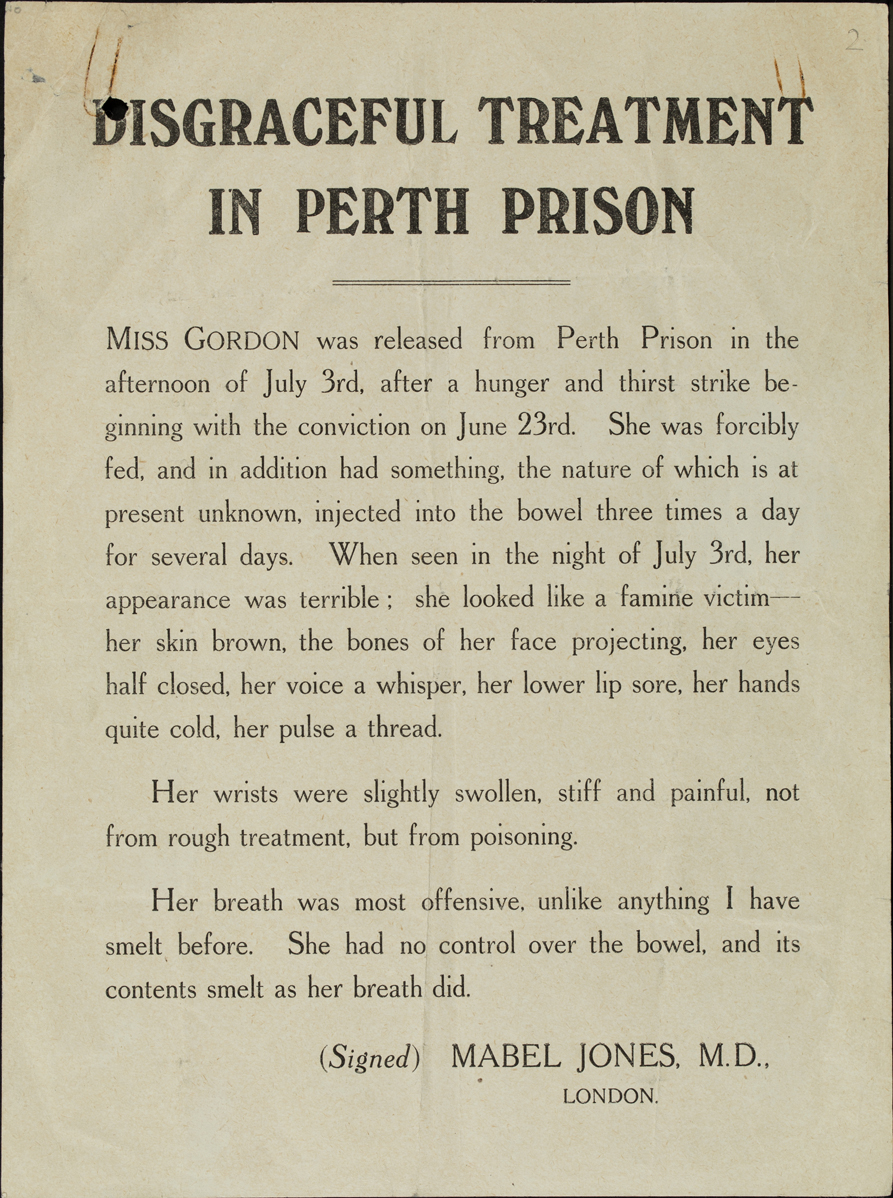

In 1914 Frances Gordon was convicted at Glasgow’s High Court of house-breaking with intent to set fire, and sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment. Gordon’s case stands out because of her treatment by Dr Ferguson Watson in Perth Prison.

As she vomited and retched shortly after admission, the decision to force-feed her was delayed. The doctor’s daily notes describe Gordon as ‘of a highly neurotic and hysterical temperament’ and detail her talking about ‘tubes and feeding‘ in her sleep.

The effects of feeding are recorded in chilling detail: Gordon’s difficulty in breathing once the feeding tube had been inserted into her ‘very narrow pharynx and nasal passage’, and how much of the food was thrown back up. Unable to successfully feed her orally, the doctor proposed to feed her ‘per bowel’ and Gordon was given a ‘nutrient enema’ of egg and milk.

This form of feeding, supplemented by additional feeding by tube, continued for four days before the doctor conceded that the prisoner’s condition was beginning ‘to cause anxiety’. Dr Ferguson Watson concludes his report by admitting that Gordon was not suitable for force-feeding but that he could not have known this until after a ‘careful trial’.

Flyer about Frances Gordon's experience of force-feeding. Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH16/46

Dr Ferguson Watson failed to anticipate the fury and criticism that reports of Gordon’s treatment would generate. Questions were raised in the House of Commons and the authorities scrambled to explain the treatment and poor condition of the prisoner upon release. The authorities appear to have convinced themselves that Gordon had undergone systemic drugging before admittance to prison. In response to the unexpected scrutiny his actions attracted, Dr Ferguson Watson claims to have suspected drugging from the start, but his notes from Gordon’s entry until her release, show that this is untrue.

Fanny Parker

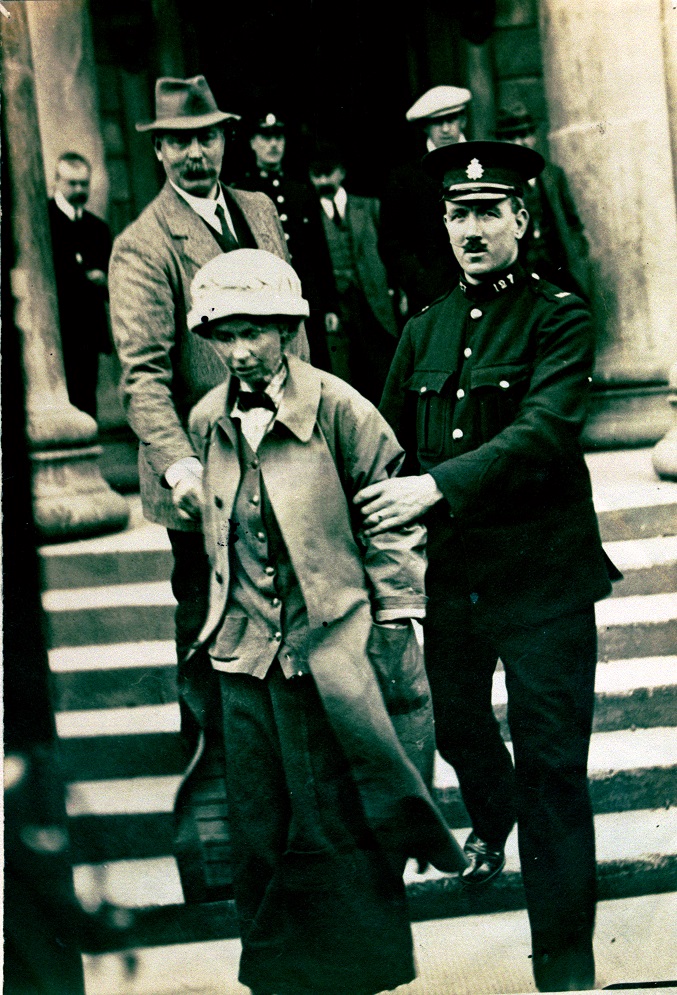

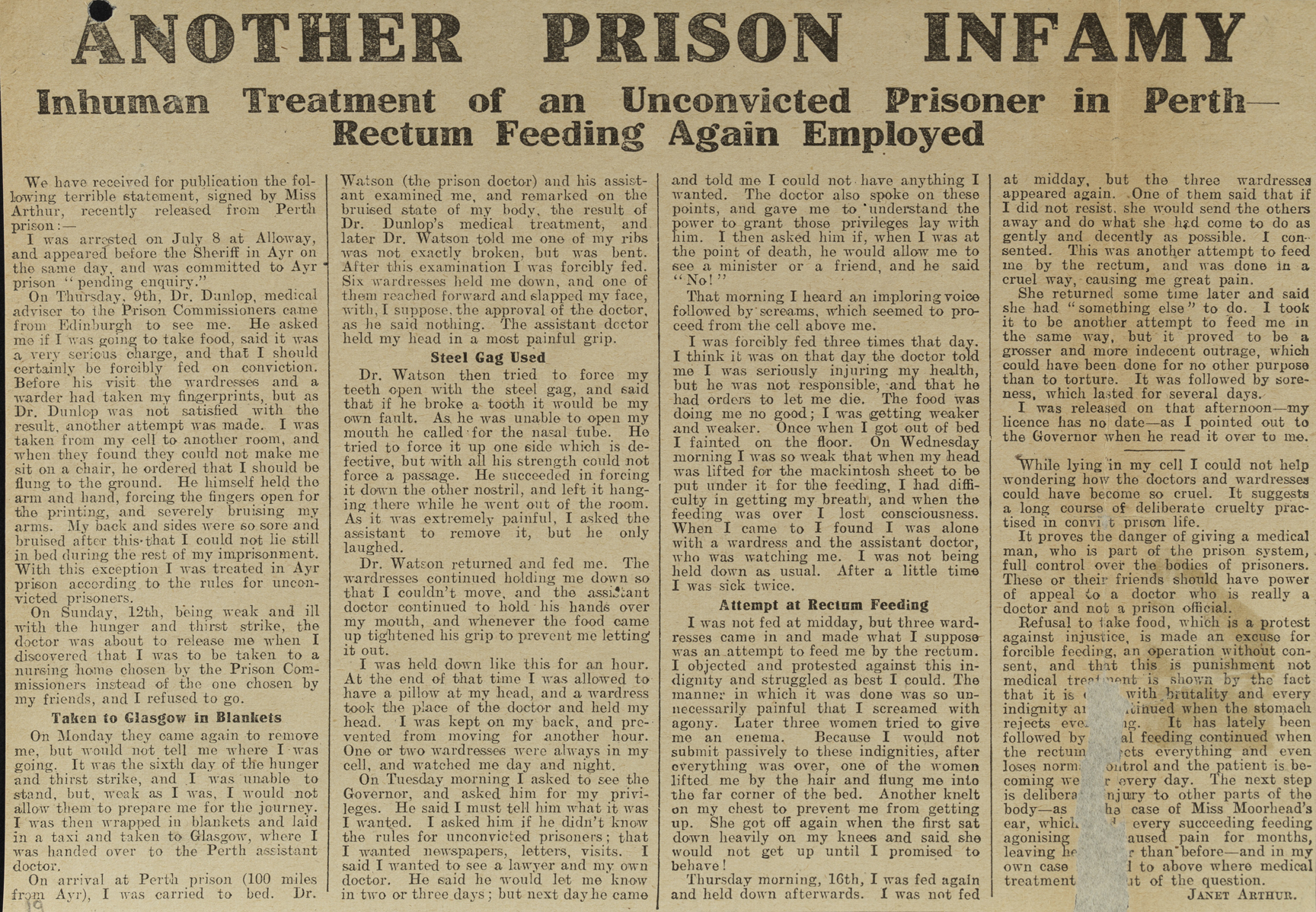

An organiser for WSPU in Dundee, Parker had been imprisoned on several occasions for damaging property. Using the alias Janet Arthur she appeared in Ayr Court 9 July 1914, accused of attempting to blow up Robert Burns’ Cottage in Alloway. She refused to enter the dock or to recognise the court’s jurisdiction and Parker was committed to Ayr Prison pending further inquiry.

Photograph of Fanny Parker, alias Janet Arthur, being escorted from Ayr Sheriff Court by a police officer, 1914. Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH16/43

Parker immediately went on hunger strike and after four days was transferred to Perth Prison to be force-fed, still untried. Despite the furore that Gordon’s treatment had recently caused, Parker was judged fit for feeding, and this was once again attempted by rectum. This occurred seven times over the following four days before her family intervened. She was the niece of Lord Kitchener and the files show her brother, Captain Parker, contacting and negotiating with the authorities for her release.

Newspaper report of Fanny Parker's experience of force-feeding, August 1914. Crown copyright, National Records of Scotalnd, HH16/43

Parker is unique in that her family was influential enough to arrange for a second, independent, doctor to examine her. In comparison to Dr Ferguson Watson’s reports that her ‘condition [was] satisfactory’, the comments of Dr Chalmers Watson are very different, stating that Parker was in a state of ‘pronounced collapse’. Dr Chalmers Watson's comments on her condition, and the apparent damage to Parker’s genitals in the process of force-feeding, indicate her distaste for this method of ‘treatment’.

Milestones on the road to equality

Women at War

After the outbreak of war, action for suffrage was mostly set aside. While some suffragists joined anti-war groups, most women campaigners diverted their energy and organisational skills into supporting servicemen’s families, nursing and other voluntary work. The Scottish Women’s Hospitals, founded by Dr Elsie Inglis, were among the more remarkable humanitarian and patriotic efforts. Women replaced men in many workplaces across Britain, for example as tram drivers and workers in factories and even in heavy engineering.

Wartime women workers at John Brown & Co’s shipyard. The message reads: ‘When the boys come [back] we are not going to keep you any longer Girls.’ Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland , UCS1/118/GEN/393/10

Women get the vote 1918

Change came in 1917 when it was realised millions of servicemen would be returning home only to find they were technically barred from voting. Lloyd George’s government was forced to remove the property qualification for male voters, and initiated conferences on women’s suffrage. On being consulted, the NUWSS and WFL reluctantly agreed to a minimum age of 30 and property qualifications. These were the main conditions of women’s enfranchisement in the Representation of the People Act, which came into force on 6 February 1918.

A Gender Bar Removed 1919

Although women had taken on an unprecedented range of work during the war, formal barriers still barred them from public roles and jobs, and the professions. This began to change in 1919 with the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act.

The Act made the most difference to unmarried and educated women who could now pursue careers in professions such as the law, medicine and the civil service. Some professions were slow to accept women at all, let alone on an equal footing. Although women did not enjoy access to all jobs and workplaces, it was a step on the unfinished journey towards equality in employment.

In 1921 a Scot, Madge Easton Anderson (1896-1982), was the first woman in Britain to qualify as a solicitor. She was also the first Scottish woman to qualify for practice in England, 1937, and was a partner in Britain’s first all-female law practice.

In 1923 Margaret Kidd (1900-1989) was the first woman called to the Scottish bar, in 1948 Britain’s first female King’s Counsel, and the first female Sheriff Principal in 1960.

Women Jurors 1921

The law changed to allow women aged between 21 and 60 years, and who met the same property qualifications as men, to sit on juries. They first did so on 10 March 1921 in Edinburgh Sheriff Court. On 29 March the first High Court trials with women jurors were held in Inverness. The mixed jury of 15 reached verdicts in three cases of sexual crimes. Male sceptics feared women would be shocked by court cases and physically unable to endure them.

Most female jurors were married, middle-aged and had the vote. However, those in their twenties might serve in a criminal trial involving the death penalty, but not be old enough or otherwise qualified for the vote.

'Votes for Women Left Out' 1928

The inconsistent minimum age for jurors and voters was one reason to lower the voting age. After the war peaceful agitation continued. In 1928 Parliament passed the Equal Franchise Act , which opened the vote to all women and men over the age of 21.

It was the culmination of decades of campaigning and a fitting achievement for the suffrage cause in all its manifestations. With some 5.24 million women added to electoral registers across Britain, a new era of greater equality began.

Further Reading

- 'Separate Spheres: The Opposition to Women's Suffrage in Britian', Brian Harrison (Routledge, 2014)

- 'A Guide Cause: The Women's Suffrage Movement in Scotland', Leah Leneman (Aberdeen University Press, 1991)

- 'The Scottish Suffragettes', Leah Leneman (NMS Publishing, 2000)

- 'Martyrs in our midst: Dundee, Perth and the forcible feeding of suffragettes', Leah Leneman (Abertay Historical Society, 1993)

- 'The Scottish Suffragettes and the Press', Sarah Pedersen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017)

- Women's History in Scotland, The Women's Suffrage Movement in Scotland 1867-1928: A Learning Resource