Surveying Scotland's Remotest Parts

Surveying Scotland's Remotest Parts

In 2020, the Scottish Government is celebrating the Year of Coasts and Waters. In this article we delve into our archives to learn more about life in remote coastal villages of the Western Isles.

By foot or by boat

Described by The Times as one of the most remote places in Western Europe, accessing the village by land meant tackling a narrow and winding four mile mountain footpath, known locally as the ‘Postman’s Path’, from the village of Urgha, a journey described by a local resident as ‘like climbing the Andes’. The ‘Postman’s Path’ was the lifeline for the village and the Royal Mail staff who walked it over the years, as it provided the only means of communication with the outside world. Accessing Rèinigeadal by sea was scarcely any easier; a fishing boat would have to be chartered in Tarbert, a perilous journey, as the lack of a harbour at Rèinigeadal meant that travellers had to ‘take their life in [their] hands’ having to jump ashore ‘often with someone on your back’.

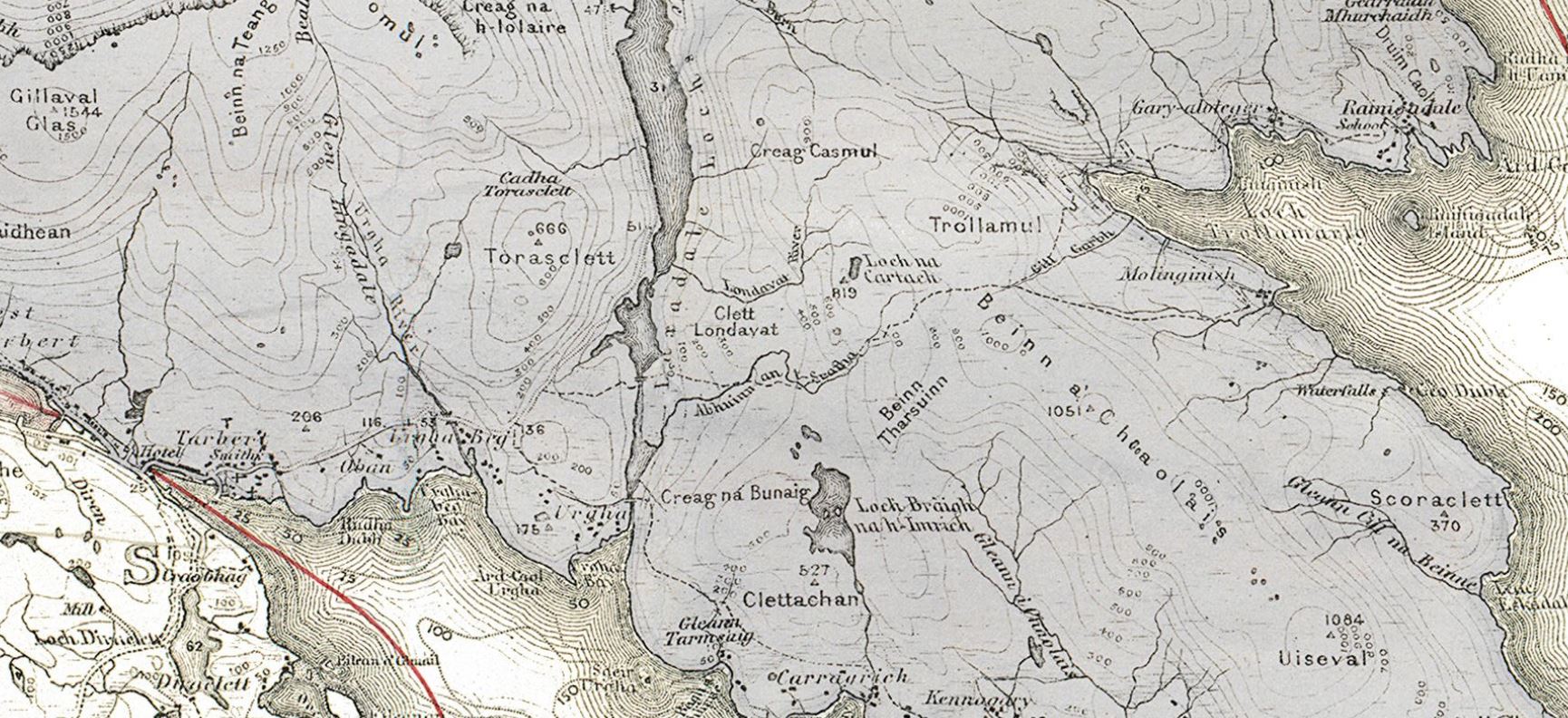

This map shows Rèinigeadal at the top right corner of the image and Tarbet at the bottom left. The Postman's Path is depicted as abroken line. Detail of Register of Sasine plan of Harris. Crown copyright. National Records of Scotland, RS230/280

Unsurprisingly, the survival of these isolated communities had long been the subject of official interest. The fate of villages like Rèinigeadal is inextricably linked to the series of forced eviction of tenant farmers across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries known as the Highland Clearances. The clearances had lasting economic and demographic consequences for communities in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, with countless people driven to emigrate, leaving the survival of many settlements in the West Highland Islands in the balance.

A modern-day Domesday

Such was the concern over the dwindling fortunes of these villages, that in 1944 the Department of Agriculture for Scotland instructed ecologist, Dr Frank Fraser Darling, to conduct ‘a modern-day Domesday’ survey of the West Highland and Islands between 1944 and 1951. This survey sought to analyse the resources of the natural environment and the social development of this remote part of Scotland.

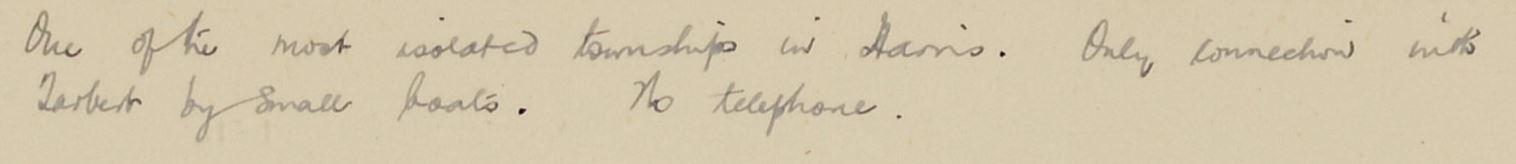

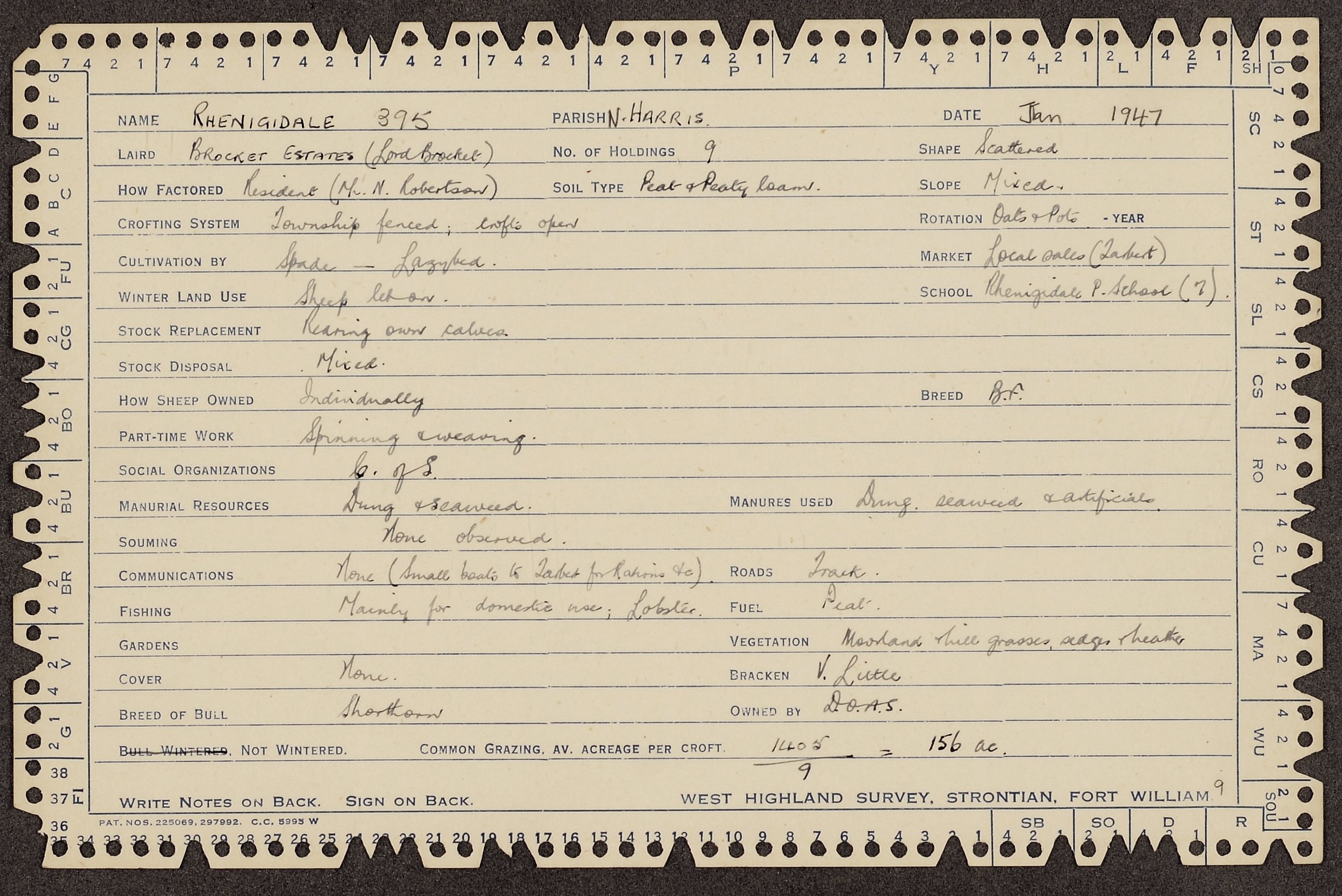

West Highland Survey card for Rèinigeadal above and below notes written on the back of the card noting the villages isolation and lack of telephone. NRS ref.: AF70/683/9-9a.

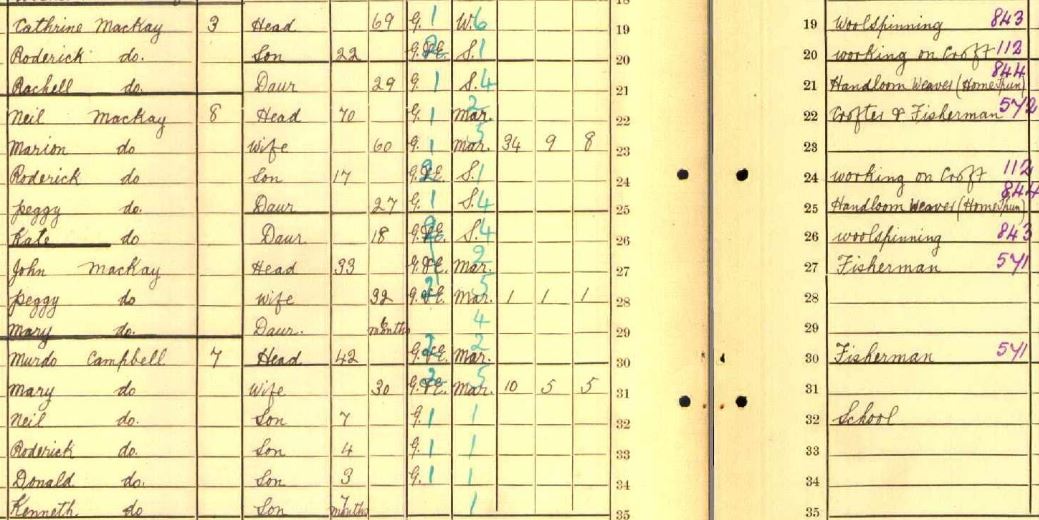

This completed West Highland Survey (WHS) card, dated January 1947, gives insight into the local occupations and landscape of Rèinigeadal after World War Two. It indicates that fishing and small-scale farming or crofting as it is known in Scotland, were the main sources of income, with wool spinning generating additional earnings. What is striking is how little the economic makeup of Rèinigeadal had changed from the mid-nineteenth century. If we cross-reference this document with census returns from 1841, 1871 and 1911 we find very similar patterns of employment with the majority of the male inhabitants listed as fishermen and crofters and the womenfolk as weavers or spinners.

Detail from 1911 Census return for Rèinigeadal. Examples of listed ocupations are 'crofter & fisherman', 'woolspinner' and 'handloom weaver'. ScotlandsPeople ref.: 111/1 10/2.

Rèinigeadal experienced very little inward migration. The family names recorded on the census returns are also present in the WHS, over one hundred years later, suggesting that several generations had stayed in this isolated village. This was perhaps unsurprising given how hard it was to enter or leave. In his notes on Rèinigeadal, Darling added a handwritten note: ‘one of the most isolated townships in Harris. Only connection with Tarbert by small boats. No telephone.’

The schoolhouse

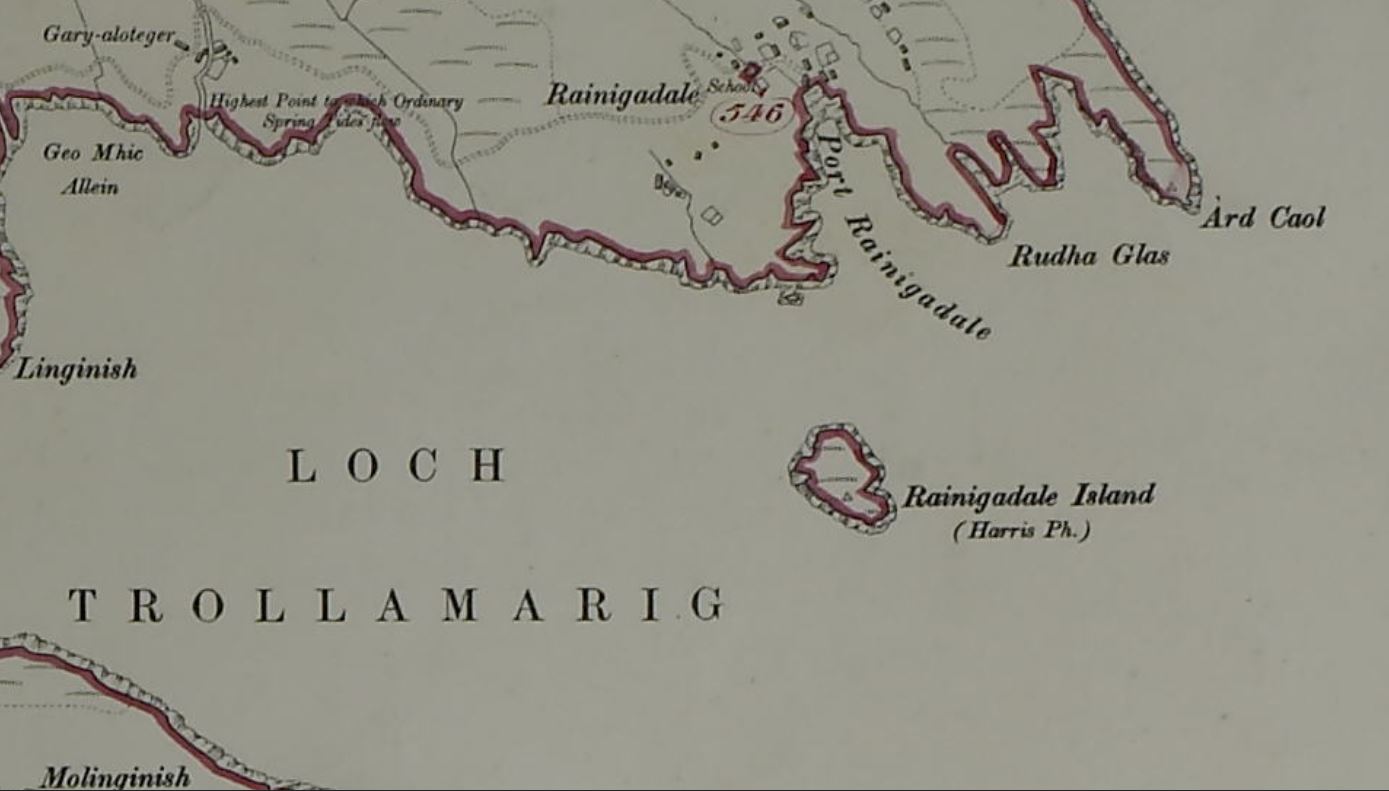

The schoolhouse is also present on the Inland Revenue Survey map, and corresponding Field Book, below. The Inland Revenue Survey took place during the years 1910-1915, and recorded land values and ownership across Scotland.

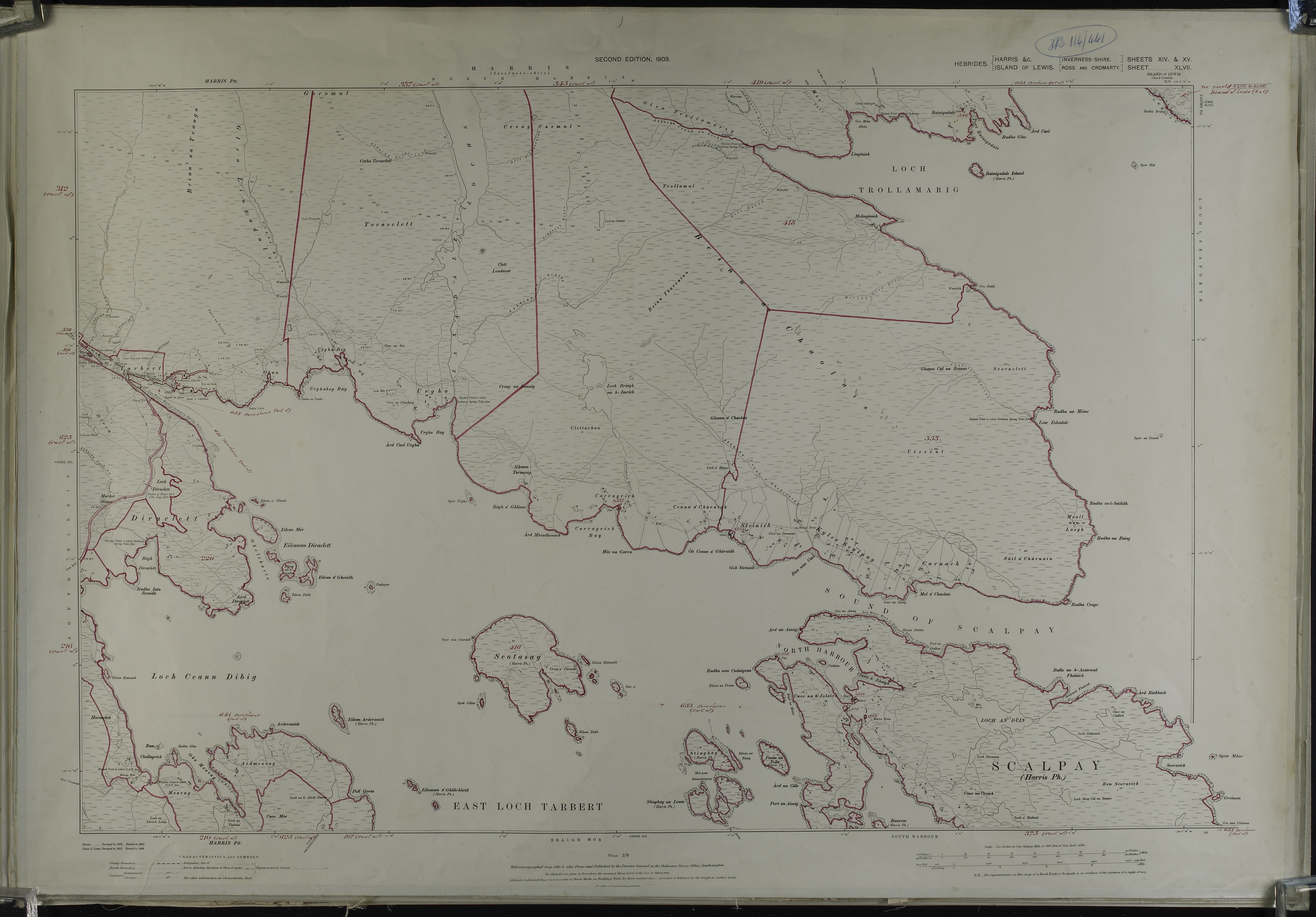

Inland Revenue Survey map of Harris and the island of Scalpay to the south. Rèinigeadal is located in the top right corner of the large scale plan. Below is a detail of the plan showing the village and the school noted. Crown copyright. National Records of Scotland, IRS114/441.

Nevertheless, it was clear from this document that the population of Rèinigeadal was in serious and long-term decline. The schoolhouse had been built for 22 pupils, but the 1911 census records that 12 children were attending school and that the total number of occupants had dwindled to 39, living in eight separate properties. By the time of the WHS, only seven students were registered at the village school. By 1970, a newspaper advertisement seeking a new teacher for the village school, indicated that only two pupils were in attendance.

The arrival of mains electricity in 1981 did little to arrest the decline, with only four houses remaining occupied. It was clear that the very existence of the village was under threat and it seemed likely, that unless serious action was taken, it would share the fate of the deserted village of Molinginis, with which Rèinigeadal shared the ‘Postman’s Path.’ One long term advocate for improving access to Rèinigeadal had been local resident and postman, Kenny MacKay. Mr Mackay had spent nearly two decades arguing that the only way to save his village was for a road to be built between Rèinigeadal and Tarbert. Eventually in late 1979, the Western Council Transportation Committee agreed to the scheme. It was decided that a single-track road, linking with the A859 would be built. However, it would be another decade before this would be constructed and by the time it opened the population of Rèinigeadal was only 11.

Amongst those celebrating the decision was Moira Laird, Rèinigeadal’s schoolteacher and Kenny MacKay’s fiancé, who in an article by The Aberdeen Press & Journal covering the council decision in 1979, declared herself ‘delighted’. Nevertheless, the arrival of the road a decade later, would have profound consequences for the schoolteacher. Creating a road route to Tarbert meant that the school in Rèinigeadal, with only one pupil on the roll (Ms Laird’s own son Duncan) was deemed unviable and closed. Arrangements were made to transport him 12 miles by bus to the nearest school.

This local bus service is now utilised by the local children and tourists alike, and the much yearned for road appears to have encouraged visitors to experience this scenic yet remote part of Scotland. The old path to Tarbert is still well-trodden, but now popular with ramblers and mountain bikers. The village hostel welcomes international guests and Moira Laird’s old schoolhouse has become self-catering accommodation. New houses have been built for families seeking to escape city life, in the beautifully stark landscape of Harris’s dramatic coastline.

Resources used:

National Records of Scotland, Duplicate Register of Plans series

National Records of Scotland, Inland Revenue Survey Maps and Field Books

National Records of Scotland, West Highland Survey Report

ScotlandsPeople, Census Returns

The Times [London, England] 27 Apr. 1989: 5. The Times Digital Archive

The Aberdeen Press and Journal. 21 Dec. 1989. British Newspaper Archive

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Dr Frank Moss Fraser Darling