John Edmonstone: Enslaved Man to (free as a) Bird-Stuffer

John Edmonstone: Enslaved Man to (free as a) Bird-Stuffer

How did a freed enslaved man from Guyana inspire a young Charles Darwin to study naturalism rather than medicine above his Edinburgh taxidermy shop? As part of Black History Month, we have explored our archives to see if we could discover more about the life of John Edmonstone; a Guyanese enslaved individual who settled in Scotland and started a successful taxidermy business.

John Edmonstone was born in what was then known as British Guyana, a British colony at the time, located at the northern tip of South America. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Guyanese economy was largely founded on the production of sugar, which at the time of John’s birth, was largely dependent on enslaved labour. Scots were prominent among these plantation owners, including Charles Edmonstone of Cardross in Dunbartonshire (1782-1865). Charles Edmonstone owned the wood plantation in the Demerera region of Guyana on which John was born into slavery. As was common, John was given the last name of his slave-owner.

Little is known about John Edmonstone’s early life, until he met with the naturalist and explorer Charles Waterton (1782-1865), during Waterton’s travels in South America. Waterton, a friend and later son-in-law of Charles Edmonstone, is known as a conservationist and for introducing curare to Europe, a paralyzing plant extract that was subsequently an anaesthetic used in surgical operations. A true eccentric, Waterton also talked to insects he encountered and even rode an alligator. During a visit to his friend Charles Edmonstone’s plantation around 1812, Waterton began gathering and studying specimens from the surrounding jungle. To preserve as many examples of exotic birds as possible, Waterton taught ‘John, the black slave of my friend Mr Edmonstone, the proper way to do birds’ (Waterton, Wanderings in South America). Waterton describes teaching John the art of taxidermy as a lengthy task, as the latter did not take up the practice easily.

In 1817, John travelled to Scotland with his master, presumably to continue a life of servitude at Cardross Park with the Edmonstone family. Waterton states that Charles Edmonstone ‘took him [John] to Scotland, where, becoming free, John left him,’ and that he took up employment at the ‘Glasgow and then the Edinburgh Museum'. The act of transporting John from the plantation to a liberated Scotland suggests that John had earned a degree of favouritism from his slave-owner, and this may have resulted in his emancipation through manumission (liberation granted at slave owner’s discretion). The other possibility is that John bought his freedom from his master, although by the early 1800s this process was becoming less common.

John's life in Scotland is easier to trace. We can learn of John’s whereabouts in Scotland by consulting the Post Office Directories which list inhabitants, their addresses and professions. In 1823, John Edmonstone ‘bird-stuffer’ had set up a shop at 37 Lothian Street, close to the University of Edinburgh buildings. John found his skills were much in demand, especially given the fashion for taxidermy in the nineteenth century, and he was able to build a successful business for himself.

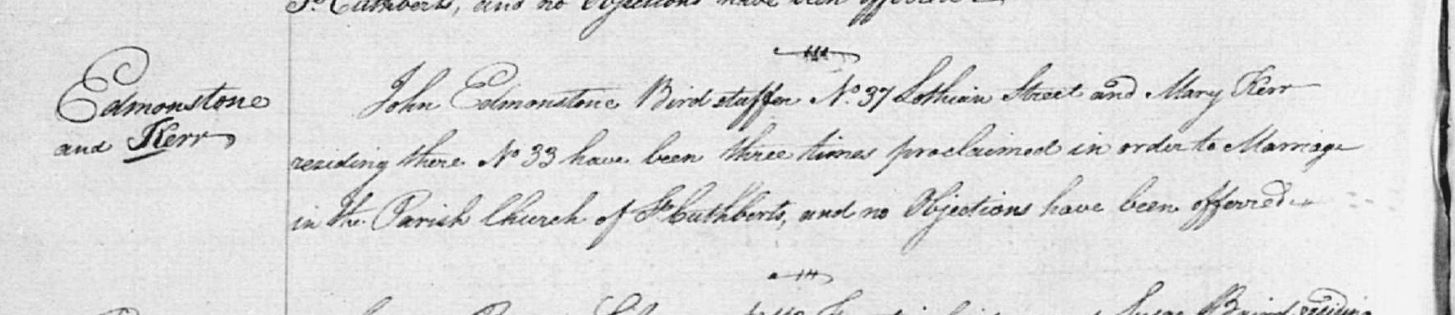

With his business taking off, John met Mary Kerr, a fellow resident of Lothian Street. In family history records held by the National Records of Scotland, we have found a proclamation of banns for John Edmonstone and Mary Kerr. This was recorded in the parish of St Cuthbert’s on 12 December 1824:

Proclamation of banns for John Edmonstone ‘Birdstuffer’ and Mary Kerr, 12 December 1824.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, OPR 685/2 400 page 652, St Cuthbert’s.

However, it is not confirmed that the marriage was conducted at the church. In this particular register of St Cuthbert’s parish, it was customary to annotate the banns entry underneath, with a note of the person conducting the marriage service, the date and place of the marriage. It is possible that a betrothal had taken place elsewhere, without any official record of the event, as permitted by Scots law. However, as no children of John and Mary have been traced, it is thought unlikely that the marriage took place.

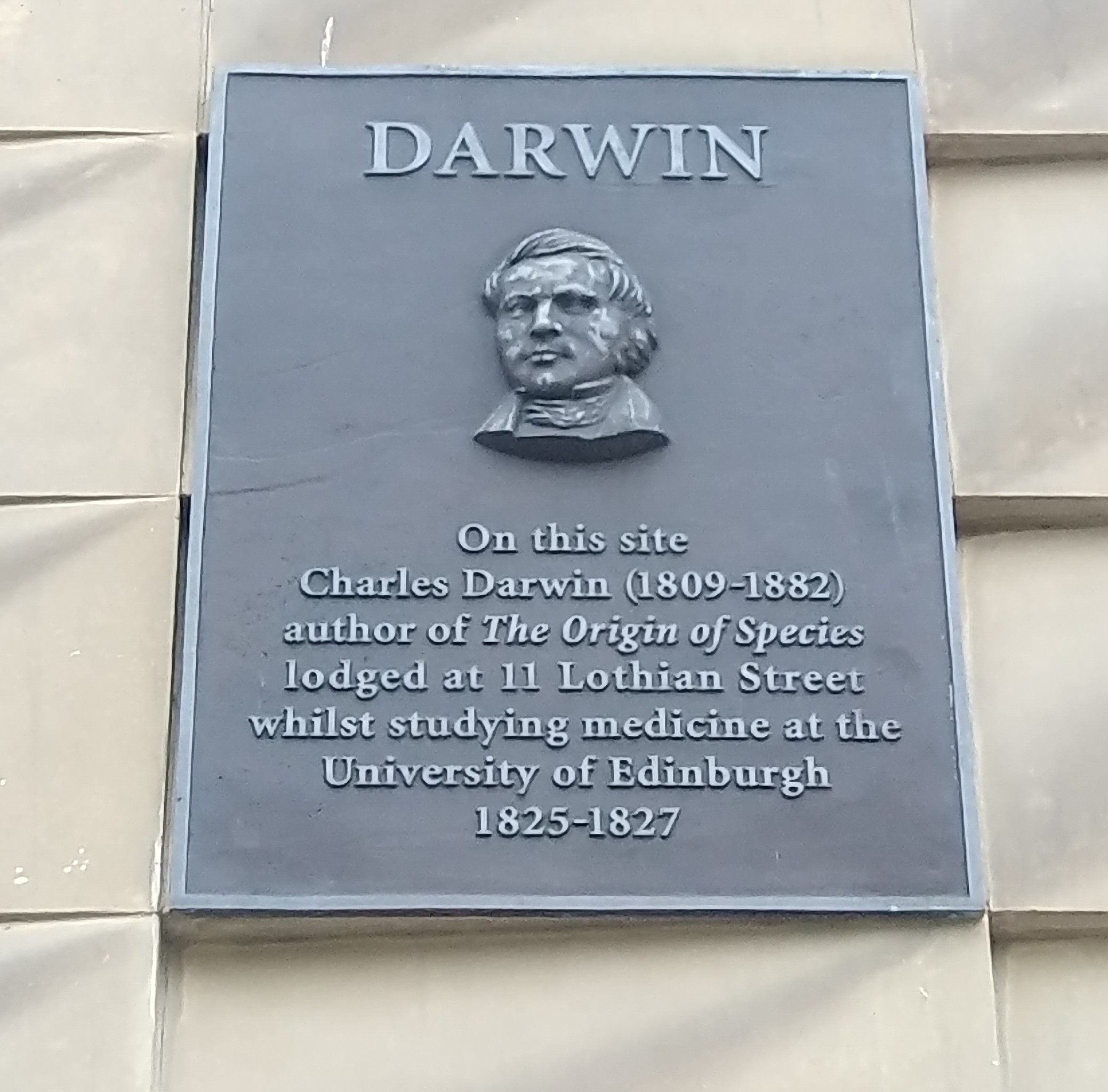

It was at this shop on Lothian Street in 1826, that a sixteen-year-old medical student by the name of Charles Darwin, took instruction from a ‘negro [who] lived in Edinburgh, who had travelled with Waterton, and received his livelihood via stuffing birds, which he did excellently’. Darwin was studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh Medical School and lodging with his brother, Erasmus, at number 11 Lothian Street. However, Darwin explained to his sister in a letter of 29 January 1826, that he was introduced or recommended to John Edmonstone and his talents by an acquaintance.

‘I am going to learn to stuff birds, from a blackamoor [sic] I believe an old servant of Dr Duncan.’

Dr Andrew Duncan was an eminent physician and professor at the University of Edinburgh, but unlikely to have taught Darwin himself, being in his early 80s when Darwin matriculated.

Darwin was disillusioned with his medical studies and enjoyed ‘often to sit with him [John Edmonstone]’ and learn to ‘stuff birds’ for a charge of 'one guinea, for an hour every day for two months'. It is likely that during these regular sessions John and Darwin discussed the varieties of birds and mammals of South America and may have even inspired Darwin to study these creatures first hand. Five years later, Darwin was to set sail on HMS Beagle, and survey the coast of South America. The studies carried out on this voyage, utilised the taxidermy skills Darwin had learned directly from John Edmonstone. The voyage to South America was foundational to Darwin’s development and in his work ‘The Voyage of the Beagle’ Darwin asserted that it was on the South American voyage that he expanded his knowledge of natural history. These skills, developed in part thanks to John Edmonstone, allowed Darwin to develop the theory of evolution as laid out in ‘The Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life’ (1859). Darwin visited Waterton in 1845, and described Waterton as ‘the strangest mixture of extreme kindness, harshness & bigotry, that I ever saw’. One wonders if John Edmonstone came up in conversation and if they exchanged memories of him.

Plaque commemorating Darwin’s residency on Lothian Street, Edinburgh.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland.

The popularity of taxidermy as part of interior design was emerging at this time, and Queen Victoria herself accumulated a large collection of stuffed animals, and in particular, birds. As a consequence, business must have been brisk, as John moved to presumably more prominent located in the main shopping thoroughfare of South St David’s Street and Princes Street between 1826 and 1843. John appears in the Electoral Register of 1835, giving his address of South St David’s Street.

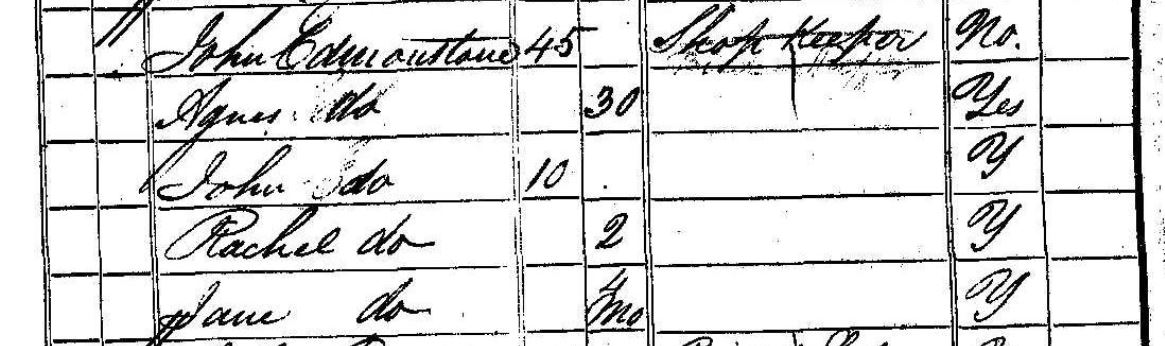

We have also possibly found a census record of a John Edmonstone was enumerated in the 1841 census living at 7 James Court.

Census record for John Edmonstone, aged 45, Shop Keeper in 1841.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, census record 685/1 171 page 5.

We cannot say with absolute certainty that this is the same John Edmonstone, but the evidence is strong. The census states, that the cited John Edmonstone is a shop keeper and that John Edmonstone, unlike his wife and children, was born outside Scotland, as is the rest of the family. Frustratingly, the entry does not record place of birth. The last column of the entry which asks ‘Whether Foreigner, or whether Born in England or Ireland’ is left blank. The often-incomplete nature of census records of this period hampered our attempts to trace a marriage certificate for John and Agnes. Nor could birth certificates be found for any of their three children.

After 1843, all trace of John Edmonstone and his possible family disappears and whilst we cannot tell the full story of John Edmonstone's life, we have tantalising glimpses of how he fitted into the academic and business world of early nineteenth-century Edinburgh. He was a successful business man, tutor and mentor, who earned enough to register to vote and in all likelihood established a family of his own in Scotland.

In 2009 John’s life was commemorated with the installation of a plaque at the location of his Lothian Street shop, just a few doors down from the plaque marking the achivements of his own one time student, Charles Darwin. John’s plaque, however, has since disappeared, presumed stolen, but we hope these new insights into John’s life bring more awareness of his story and place in Scottish history.

Resources used:

Charles Darwin, The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1887

Brian W. Edginton, Charles Waterton: A Biography, 1996

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 22,” https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/DCP-LETT-22.xml

R.B. Freeman, ‘Darwin’s Negro Bird-Stuffer’, Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 33, No.1, August 1978

Poll Book for Councillors of the City of Edinburgh, 1835.

Charles Waterton, Wanderings in South America, 1825