Defying the Scottish Weather – A Brief History of Growing Exotic Fruit in Scotland

Defying the Scottish Weather – A Brief History of Growing Exotic Fruit in Scotland

Over the last 350 years, the landscape of Scotland has transformed from a swampy moorland to that of a structured inhabited land, incorporating a patchwork of bordered fields, stretches of trees and planted gardens. This article looks into the popularity of growing new and exotic fruits in 18th century Scotland, and the innovative methods employed to successfully grow exotic plants and fruits such as the pineapple, figs and palms.

Before the 17th century ornamental or pleasure gardens were exclusively sited on monastic or royal lands. However, with the upper and middle classes prospering in mid-17th century Scotland, these groups began to invest heavily in their homes and gardens. The ability to travel widely across Europe and beyond, saw an appetite for introducing plant and fruit varieties grown in warmer climates and enterprising Scots sought ways of growing exotic fruit and vegetables on home turf. One such method was the walled garden - particularly popular in Scotland - which sheltered plants from strong winds, the walls absorbing heat from the sun during the day and creating a temperate enclosure. Walled gardens allowed flowers and produce for the house to be grown successfully. The planting of trees or shrubs close to a south facing wall, known as ‘fruit walls’ could create a microclimate within the garden, allowing soft fruit, such as figs or peaches to be grown.

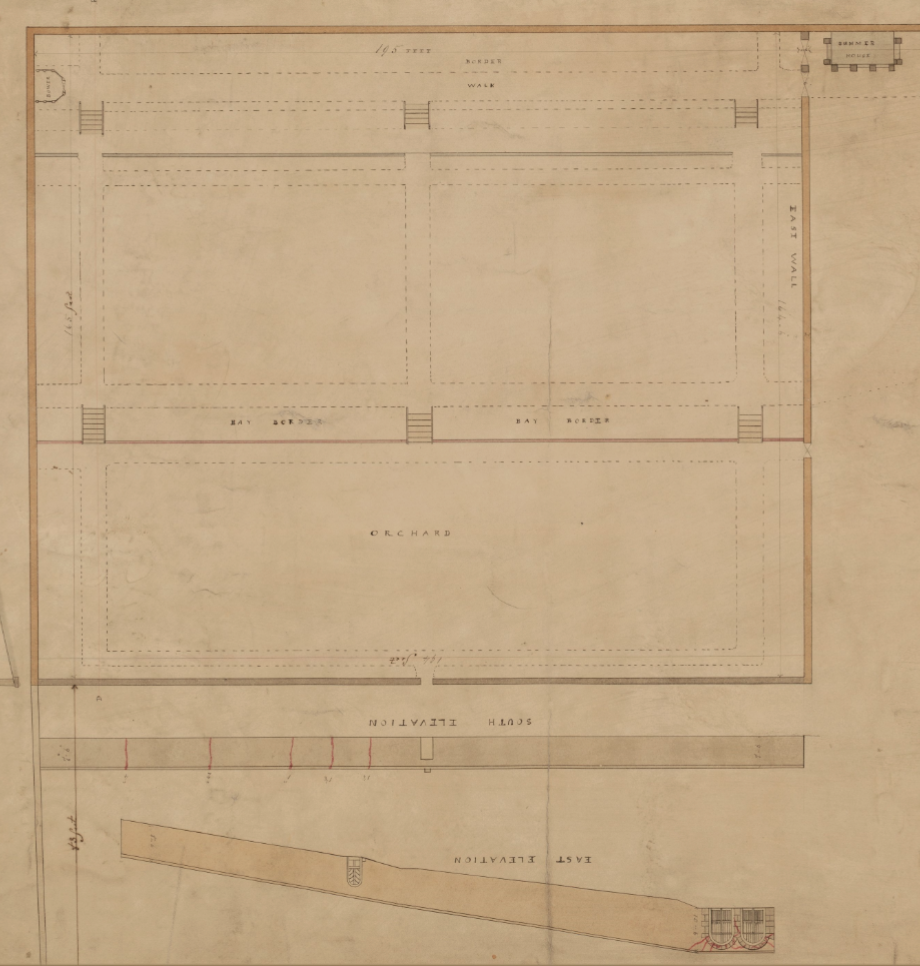

Detail of plan showing walled gardens at Carsebridge House, Alloa, 1853. Sections were marked for an orchard and bay borders. National Records of Scotland, RHP151/5

Taymouth Castle, the seat of the Campbells of Breadalbane, near Loch Tay was an extensive private garden, featuring sectioned walled gardens, glasshouses with stoves, a Palm House, several peach-houses and seven vineries. Not surprisingly, it was noted in 1798 that ‘More help of hands in the garden and nursery are wanted as 4 men are not able to do the work in the weeding season.’ (National Records of Scotland, GD112/20/1/31/17, dated 14 May 1798).

One particular fruit became a fashionable commodity in the upper echelons of mid-17th century society – the pineapple. Regarded as a symbol of prosperity, presumably because the fruit was scarce and expensive to buy (late 17th century prices recorded pineapples costing 8 shillings per pound or £45 in today's money), having a pineapple at the centre of the dining table was an opportunity to communicate social standing to invited guests.

Pineapples had been successfully grown in mainland Europe from the late 16th century onwards, but it took the invention of the hot house in the second half of the 17th century for mass pineapple cultivation in Scotland to become possible. The first pineapple propagated in Scotland is attributed to James Justice in 1728. Justice was a principal clerk of the Court of Session, but his passion for gardening resulted in a ‘garden paradise’ created at Crighton House, just south of Edinburgh. Justice was an innovator of growing methods of pineapples or ‘ananas’, designing a pineapple stove for forcing the fruit.

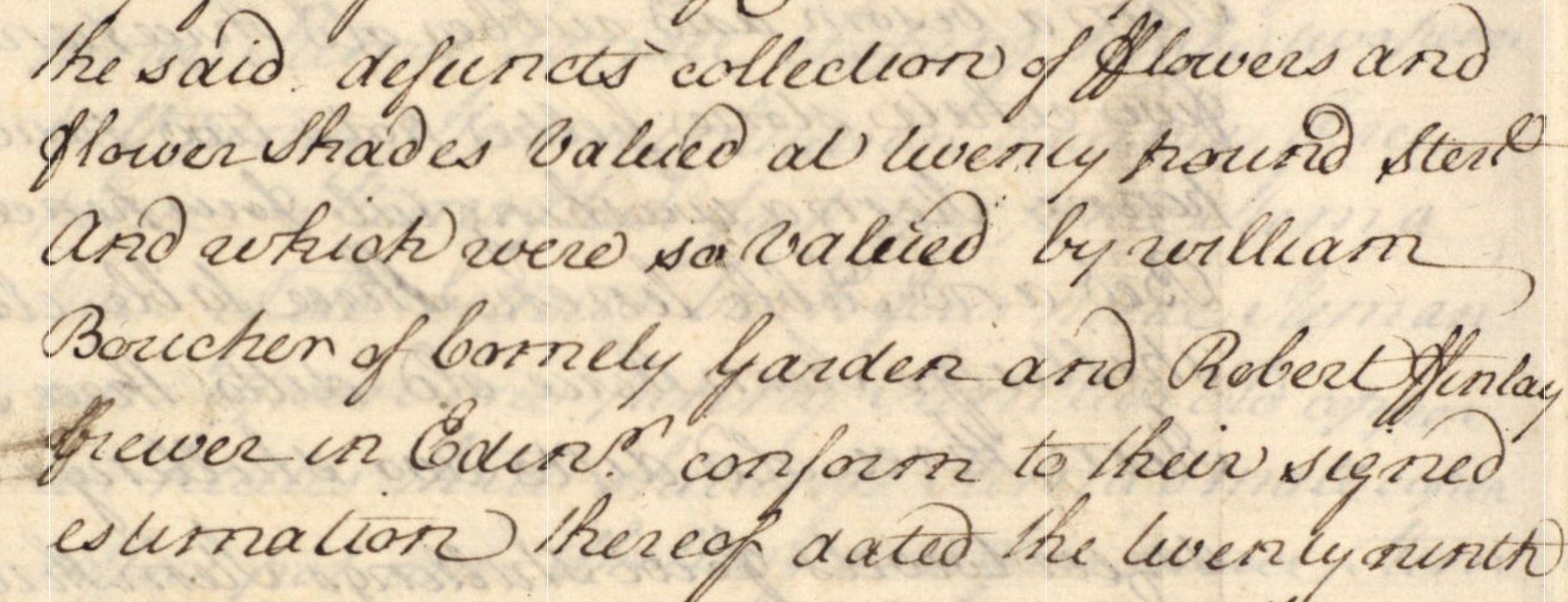

Justice shared his plan for the stove and other horticultural experiments in his publication 'The Scots Gardiners Director’ (1754) and also wrote further works on gardening in Britain. Justice was considered the father of Scottish gardening but his spending on his ‘hobby’ outweighed his income, and he acquired great debts. At the time of his death in 1763, Justice’s gardening accomplice, William Boucher, of Comely Garden, near Holyrood, was called upon to value Justice’s garden.

Extract from Justice's will, detailing the defuncts [deceased] collection of 'flowers and flower shades' valued by fellow gardeners Boucher and Finlay at 20 pounds sterling - greater than £2,000 in today's money. National Records of Scotland, Commissary Court records CC8/8/119 pp. 772 - 779 via ScotlandsPeople website

Gardeners who were successful in growing ‘exoticks’ such as the pineapple were in high demand by the aristocracy, who demanded the fruit all year round. Promises of pineapple at the dining table to lure the most distinguished guests were even mentioned in dinner invitations. Pineapples were in such high demand that they could be hired as a display item for an appearance at the centre of a dining table. Pineapples could be returned to the vendor uneaten, or for a significant mark-up, could be consumed by the guests. The status of the pineapple at dinner parties of the 18th century is highlighted by an invitation sent by Mrs C Strickland of Sizergh Castle in Cumbria to a Mrs Hutton, dated September 1772, highlighting such culinary delights as ‘venison and a pineapple’ (NRS, GD254/1045). Pineapple cultivation was big business, and contemporary gardeners published guides to building pineries, sharing tips on their achievements.

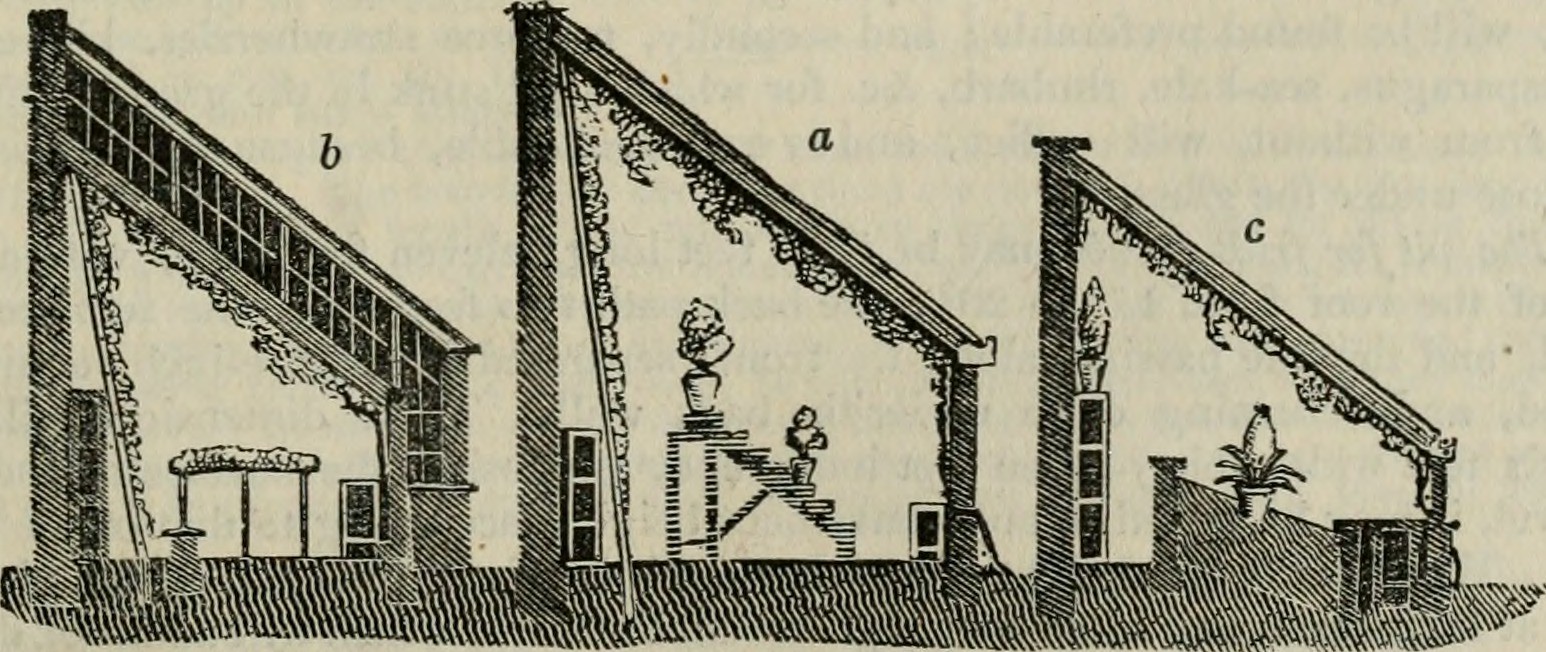

John Hope, the Keeper of the Botanical Gardens in Edinburgh, visited Hamilton Garden in October 1765, and noted that it had a 12 foot high brick wall round two sides, 300 feet at top heated by six furnaces. However, the Pinery he considered faulty, `Nothing in it but pines cockscombs, capsicums and arums' (NRS, GD253/144/4). There were two methods of growing pineapples. The first was to build ‘fire walls’ supplied by coal burning stoves which supplied heat via flues in the walls, as seen in the Crichton pineapple stove plan, above. Many early stoves burnt down, as build up in the flues caught fire. A safer option was to dig deep pits filled with manure and topped with bark to generate temperatures of 25-30 degrees Celsius to encourage the fruit to grow.

Illustration of pine stoves from C. Loudon's 'An Enclyclopaedia of Gardening', 1822. Image credit: www.archive.org

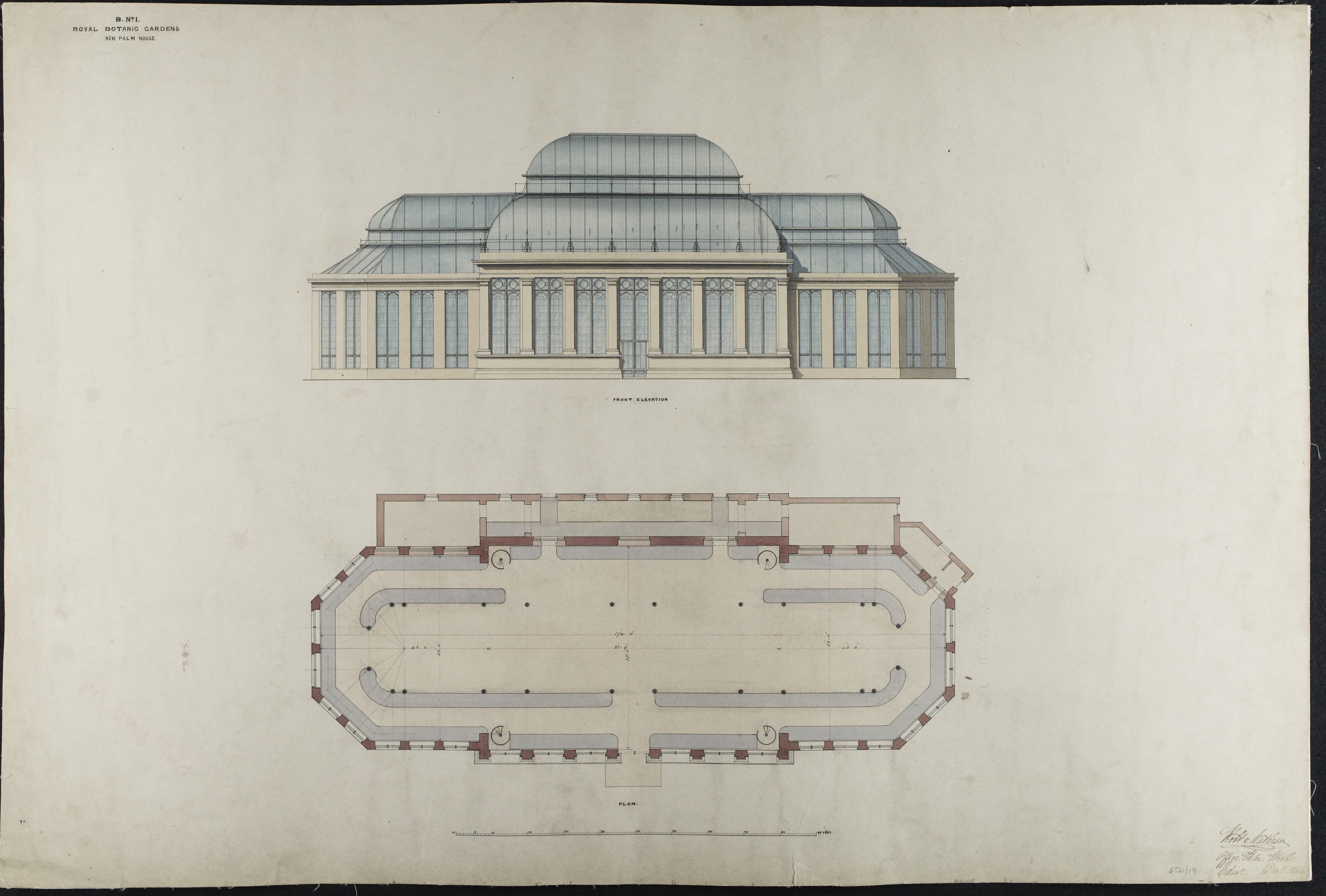

The cultivation of pineapples across northern Europe developed rapidly in the 19th century. The introduction of hot water heating systems and the invention of sheet glass to construct large glass houses which could accommodate thousands of fruits, saw an expansion in the scope and scale of pineapple cultivation in Scotland. An example can be seen today at Edinburgh’s Royal Botanical Gardens. The Temperate Palm House built in 1858, is the tallest Palm House in Britain at a height of 21.95m. Alongside the pineapples, a variety of plants were grown here, including banana, figs and sugar cane.

Architectural plan of the New Palm House at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh. National Records of Scotland, RHP6521/19)

Pineapples were displayed at exhibitions up until the early 1900s. However, cultivating the fruit on home soil dwindled, as canned imports were readily available and a cheaper alternative than the time consuming and expensive process of growing the fruit on home soil. The legacy of Scotland’s love affair with the pineapple can still be seen at Dunmore, Stirlingshire the seat of John Murray, Earl of Dunmore. This site was part of the kitchen garden and includes a sizeable stone monument to the ‘King of Fruits’ which still amazes visitors today.

The Dunmore Pineapple, where at one time scores of pineapples were successfully grown by the Earl of Dunmore, near Airth, Stirlingshire. Photo credit: Ross on Flickr, creative commons license.

The National Records of Scotland has its own courtyard garden situated between General Register House and New Register House. This space has been transformed into a unique garden planted with 57 plant species - all connected in some way to Scotland's collective memory, whether through myth and folklore, heraldry, or association with individual famous Scots. The garden is open to visitors during our usual office hours. Admission is free. To find out more about the garden's design and plants please visit our Archivists' Garden webpages.

Resources used:

National Records of Scotland, Register House Plans (RHP)

National Records of Scotland, Register of Testaments, Commissary Court records (CC8)

National Records of Scotland, Papers of the Campbell Family, Earls of Breadalbane (GD112)

National Records of Scotland, Papers of the Lindsay family of Dowhill (GD254)

National Records of Scotland, Papers of Messrs D and JH Campbell, WS, solicitors, Edinburgh (GD253)

Fran Beauman, The Pineapple: King of Fruits, London, Vintage, 2006

Sheila Mackay, Early Scottish Gardens: A Writer’s Odyssey, Edinburgh, Polygon, 2001

Joanna Lausen-Higgins, 'A Taste for the Exotic: Pineapple cultivation in Britain', Building Conservation website

Priscilla Minay, 'James Justice (1698-1763): Eighteenth-Century Scots Horticulturist and Botanist: IV', Garden History Journal, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Summer 1976)

Botanic Stories: The Temperate Palm House, Royal Botanic Gardens website